The 29th Conference of Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has once again highlighted the critical challenges faced by developing countries in securing adequate adaptation finance. Despite fervent advocacy by groups such as the African Group of Negotiators, representing 54 African nations, the proposed sub-goal for adaptation finance under the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) was excluded from the final text.

This omission leaves developing countries scrambling for a portion of the $300 billion annual finance package promoted by the COP29 Presidency and developed nations like the European Union. Critics argue that this allocation is woefully inadequate, especially when weighed against the financial demands of implementing the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), which aims to bolster global resilience against climate impacts.

Adaptation Needs Far Outstrip Pledged Funds

For many nations, the lack of dedicated funding for adaptation measures translates to dire consequences. A representative from the Marshall Islands, speaking at the Qurultay plenary on November 21, 2024, put it bluntly:

“GGA without money means nothing for countries like mine. We published our National Adaptation Plan last year and need $35 billion for adaptation in my country alone. We are just talking about billions here while the need is in trillions. We are playing with people’s lives.”

The Marshall Islands’ requirements are emblematic of a broader issue. Developing countries collectively face adaptation financing needs of $387 billion annually until 2030, as highlighted in the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Adaptation Gap Report 2024: Come Hell and High Water.

Yet, actual finance flows remain dismal. While 2022 saw a modest increase in adaptation finance to $28 billion—up from $22 billion in 2021—this remains a fraction of what is necessary. The Glasgow Climate Pact’s target to double adaptation finance from 2019 levels ($19 billion) to $38 billion by 2025 is still far from being met, let alone the NCQG ambitions.

A Framework Without Financial Backbone

The establishment of the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (FGCR) at COP28 in Dubai last year was a step forward in defining adaptation goals. It includes seven thematic targets—spanning critical areas like water, health, food security, and cultural heritage—and four dimensional targets focused on risk assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

However, the FGCR remains toothless without substantial funding. Efforts to operationalize the framework have so far focused on developing indicators, but the resources required to implement these plans are sorely lacking. The UAE-Belem Work Programme, expected to conclude at COP30 in Brazil, aims to refine these measures further, but questions about financing loom large.

Funds Falling Short

The Adaptation Fund, which plays a key role in financing resilience projects, exemplifies the shortfall. It managed to secure just $61 million in contributions at COP29—only one-sixth of its annual target of $300 million.

Mikko Ollikainen, head of the Adaptation Fund, underscored the gravity of the situation: “The actual need for adaptation is in the range of $200-$400 billion, and so far, we’ve only received 10% of the target.”

The Adaptation Fund’s struggle mirrors the broader disconnect between developed nations’ commitments and the actual needs of vulnerable countries.

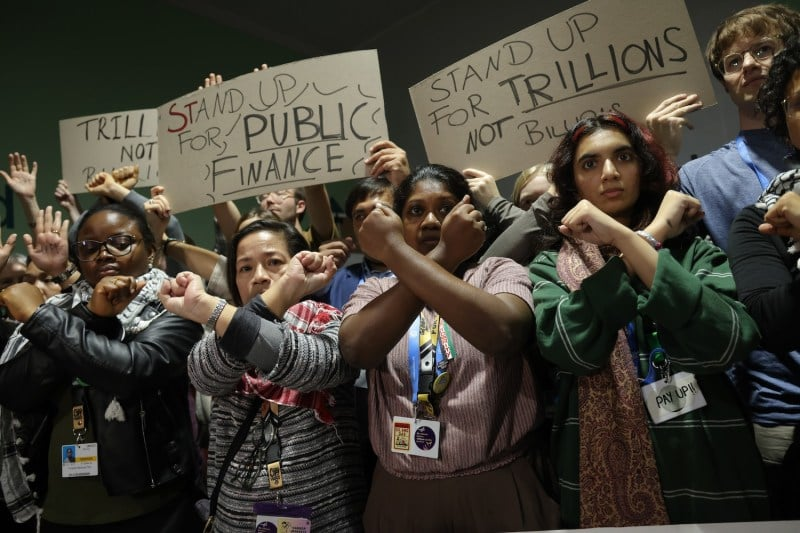

A Call for Urgent Action

As the world moves closer to the deadlines set by various climate agreements, the urgency to address adaptation funding grows. UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report calls for dramatic increases in adaptation efforts and finance. However, the lukewarm response from COP29 suggests that developing nations may continue to shoulder the burden of climate resilience with minimal support.

The stakes are high, and the time to act is now. As the global community prepares for COP30 in Belem, Brazil, the hope remains that nations will move beyond rhetoric to deliver on their promises—ensuring that no country is left behind in the fight against climate change.