The Trump administration has fundamentally altered U.S. trade policy by imposing exceptionally high tariffs across a wide range of imports. While the stated reasons for these actions vary—shrinking trade deficits, countering foreign retaliation, reinforcing national security, or reshoring production—one rationale stands out for its historical resonance: raising revenue. For decades, this objective has been largely irrelevant to trade policy in advanced economies. Yet the Trump tariffs have reintroduced the idea that taxing imports can meaningfully finance government operations.

More than a century ago, tariffs played a central role in funding the U.S. government. Border taxes and targeted excise duties historically offered a straightforward, administratively simple method of revenue collection. Today, however, reliance on tariffs as a fiscal tool is characteristic mainly of younger or lower-income countries, which often lack the administrative infrastructure required for broad-based income or consumption taxes. Modern developed economies, including the United States, instead rely on personal and corporate income taxes, value-added taxes, and payroll taxes—systems capable of raising substantial revenue with relatively lower economic distortions.

Rich nations have abandoned tariffs as revenue instruments for good reason: they are among the most distortionary, inefficient ways to finance government. Tariffs either suppress economic activity and therefore weaken the overall tax base, or they trigger costly efforts to circumvent the tax, reducing revenue while still imposing economic harm. In the United States, the August 2025 tariff revenue total of roughly $30 billion illustrates the large fiscal stakes involved. But transforming these revenues into a long-term stream comes with major costs: higher prices for consumers, reduced competitiveness for American firms, slower economic growth, and strained diplomatic relations.

Recent Trends in Tariff Revenue

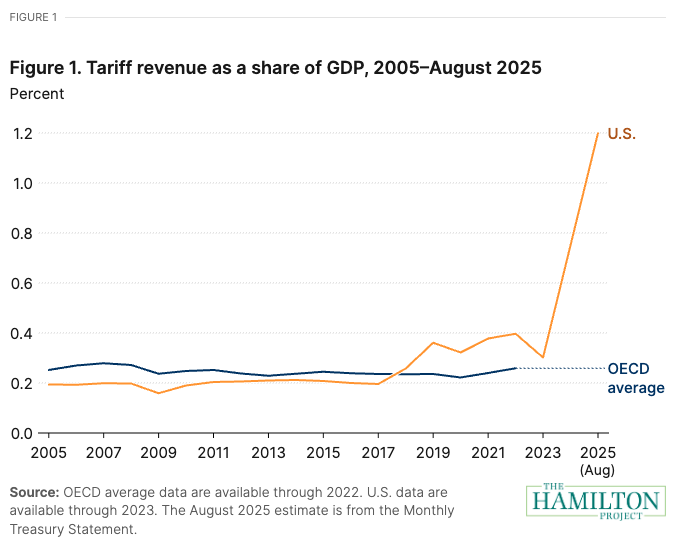

Beginning in 2018, the United States sharply increased tariff collections, pushing U.S. tariff revenue as a share of GDP above the OECD average for the first time in decades. By August 2025, U.S. tariff revenue exceeded 1 percent of GDP—a level more than five times higher than a decade earlier and nearly five times the OECD average. Only a handful of countries collect tariff revenue on this scale, and they are predominantly small island states or low-income nations for whom trade constitutes an outsized share of economic activity.

For the United States, achieving similar levels of tariff revenue requires extremely high tariff rates that produce significant economic distortions. The OECD average for tariff-to-GDP ratios is just 0.26 percent, and the G7 average excluding the United States is even lower at 0.18 percent. By contrast, a U.S. tariff revenue ratio of 1.2 percent situates the country alongside developing economies such as Zambia and Tunisia. Unlike those nations, however, the U.S. economic structure is not conducive to raising substantial revenue from trade without steep costs.

While recent analyses—from the Yale Budget Lab, the Penn Wharton Budget Model, and others—have attempted to quantify maximum feasible tariff revenue, the core issue is not how much revenue can be collected. Instead, the question is why raising large sums through tariffs is uniquely destructive for a highly developed, deeply integrated economy like the United States.

Why Countries Trade – and Why Tariffs Disrupt That Logic

To understand why tariffs are such an inefficient revenue source, it helps to recall why trade takes place in the first instance. Countries specialize in producing goods and services for which they have comparative advantage and import items for which other nations are more efficient producers. Individuals operate according to the same logic—we no longer build our own homes, grow our own food, or produce our own energy because specialization makes us collectively wealthier.

Specialization arises from differences in technology, resource endowments, skills, and capital. Moreover, modern trade is characterized by firm-level specialization: companies around the world produce differentiated goods, from Icelandic medical devices to Japanese electronics to Italian foods. The benefits of trade include not only cost efficiency but also variety and consumer choice.

Crucially, it is typically the most productive firms that engage in trade—both exporting and importing. These firms expand when trade barriers fall, boosting aggregate productivity and raising wages for workers in those firms. Conversely, restricting trade disproportionately harms the very firms that drive innovation and growth. Thus, trade policy affects not only prices and consumer choice but also the broader trajectory of national productivity.

Why Tariffs Are an Especially Inefficient Revenue Tool

Tariffs are taxes on imported goods, and like any tax, they discourage the activity being taxed. While excise taxes on cigarettes or alcohol are intended to reduce consumption, revenue-motivated tariffs suppress economically beneficial activities. This is the first major problem with relying on tariffs for revenue: the tax base erodes as the tariff induces firms and consumers to reduce imports.

The second problem arises from the structure of the Trump administration’s tariffs. The current system applies inconsistent rates across products and countries and includes numerous exemptions. This patchwork system incentivizes firms to shift supply chains not toward the most efficient producers but toward those subject to the lowest tariff. As a result, the government often fails to collect the higher tariff it has imposed, while consumers and firms absorb higher costs from sourcing less efficient products.

Importers also legally circumvent tariffs by adjusting sourcing strategies rather than engaging in illicit transshipment. Over time, therefore, the tariff base shrinks, revenue falls, and economic distortions multiply.

Tariffs Depress Economic Growth

Trade liberalization has been widely studied, and the consensus is clear: reducing tariffs increases productivity and GDP. For example, U.S. participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership was estimated by the International Trade Commission to raise GDP by roughly 0.15–0.2 percent through modest tariff reductions.

The reverse is also true. When trade is restricted—whether through deliberate policy or unintended disruptions—productivity falls. James Feyrer’s research on the closure of the Suez Canal from 1967 to 1975 found that a 1 percent reduction in trade lowered GDP by roughly 0.25 percent. Similarly, Furceri et al. (2020) show that a 3.6-percentage-point rise in tariffs reduces output by about 0.4 percent. Extrapolating from this, a broad 10 percent tariff could reduce GDP by over 1 percent.

As of late 2024, the United States’ trade-weighted average tariff was around 20 percent, though exemptions reduced the effective rate to roughly 10.5 percent. Even at this level, a 10 percent reduction in trade could shrink the U.S. economy by 1.5 to 2.5 percent over time—implying slower annual growth by roughly 0.2 percent.

Lower growth means less tax revenue from other sources. The White House Office of Management and Budget estimates that a 1-percentage-point reduction in growth over a decade costs the federal government roughly $4 trillion. Even modest trade contraction from current tariff levels could therefore erase hundreds of billions in revenue.

Usual Responses from Tariff Supporters

Tariff advocates often claim that foreigners—not U.S. consumers—bear the cost of tariffs. While foreign producers may lower prices slightly in response to tariffs, substantial evidence shows this pass-through is incomplete. U.S. import prices have not declined meaningfully since the tariffs took effect, and early research on Trump’s first-term trade war shows that foreign firms did not significantly adjust prices.

In some cases, tariffs may cause the U.S. dollar to appreciate, partially offsetting the tariff burden. But a stronger dollar makes U.S. exports more expensive, harming exporters—often the country’s most productive firms. And when tariffs apply to imported industrial inputs, even partial price reductions cannot fully offset the higher costs passed on to American manufacturers. Ford, for example, has cited rising input costs from tariffs as a factor limiting its U.S. investment plans.

Additional Problems with Relying on Tariffs

Beyond inefficiency and slow growth, tariff-based revenue presents several other risks:

1. Tariffs Are Regressive

Low-income households spend a larger share of their income on goods rather than services, making tariffs disproportionately burdensome. Most research concludes that U.S. tariff burdens fall more heavily on lower-income consumers.

2. Broad Tariffs Undermine Strategic Trade Tools

Targeted tariffs can play a role in addressing unfair practices or protecting sensitive industries. Blanket tariff systems dilute these tools by applying costs indiscriminately.

3. Policy Uncertainty Discourages Investment

Firms cannot easily plan long-term investments when tariff regimes shift unpredictably across time, products, and countries. Faced with uncertainty, firms delay or relocate investment.

4. Modern Supply Chains Magnify the Damage

Contemporary production processes depend on globally integrated supply chains. Tariffs on intermediate goods disrupt these networks, raising production costs and reducing competitiveness.

5. Diplomatic Fallout Weakens U.S. Influence

Large, sudden tariff increases—especially when applied to allies—strain diplomatic relationships and undermine U.S. commitments to international trade agreements.

Caveats

This analysis does not claim that free trade is costless. Rapid trade liberalization can overwhelm communities and industries, and the United States has not always adequately supported displaced workers. However, abrupt contractions in trade—especially in a world defined by cross-border production networks—can be even more disruptive, forcing firms to shut down or relocate.

Moreover, the economic harm from tariffs unfolds over long horizons, making it easy to overlook in real-time data. Other large-scale developments, such as rapid investment in artificial intelligence, may mask these effects. But long-run reductions in productivity and growth accumulate steadily and materially weaken economic performance.

Tariffs, in short, are among the least efficient ways to raise government revenue. The Trump administration’s attempt to use them as a major fiscal tool imposes widespread costs on consumers, firms, and the broader economy. The United States abandoned tariff-based financing more than a century ago for compelling reasons—and reviving that approach today risks undermining both economic prosperity and international leadership.