As India marked its 77th Republic Day, Indian President Droupadi Murmu and the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi hosted an unusual pair of chief guests: Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, and António Luís Santos da Costa, president of the European Council. The two senior EU leaders reviewed the grand military parade along Kartavya Path, formerly Rajpath, amid marching contingents, cultural tableaux, and a display of hardware that underscored India’s careful navigation of great-power competition.

The display of the flags of the EU, the EU Military Staff, and our maritime missions ATALANTA and ASPIDES at India’s Republic Day is a powerful symbol of our deepening security cooperation.

— Ursula von der Leyen (@vonderleyen) January 26, 2026

It will culminate tomorrow in the signature of our Security and Defence Partnership. pic.twitter.com/l5pPxFt8Rv

The parade unfolded in a novel “phased battle array” format, the first of its kind, sequencing infantry, mechanized columns, artillery, missile systems, and aerial assets to mimic operational deployment. Overhead, Apache AH-64E attack helicopters (U.S.-origin) flew alongside indigenous Prachand light combat helicopters, while fighter formations featured a mix of French Rafales, Russian-origin MiG-29s and Su-30MKIs, and Jaguars. Transport aircraft included U.S. C-130s, P-8I maritime patrol planes, and the European C-295.

Ground elements highlighted both legacy partnerships and domestic progress. Russian-designed T-90 Bhishma main battle tanks rolled alongside the indigenous Arjun tank. Missile systems on display or featured in tableaux included the joint Indo-Russian BrahMos supersonic cruise missile, the fully indigenous Akash surface-to-air missile, and, for the first time in public view, the Russian S-400 long-range air defense system.

A tri-services tableau devoted to “Operation Sindoor”, the four-day India-Pakistan confrontation last year, featured the S-400 prominently, alongside Rafales armed with Scalp missiles and Su-30s, illustrating its reported role in neutralizing Pakistani aircraft and missiles at extended ranges.

Rafale, Su-30MKI Showcase Air Power Over Kartavya Path

— DD News (@DDNewslive) January 26, 2026

From the deserts of Rajasthan to the skies above Kartavya Path, Rafale and Su-30MKI fighters from Air Force Station Jodhpur displayed precision, reach and air dominance during the Republic Day flypast. The iconic Sindoor,… pic.twitter.com/CfKpur4TSN

New indigenous debuts captured particular attention. The Long Range Anti-Ship Hypersonic Missile (LR-AShM), or hypersonic glide vehicle, capable of Mach 10 speeds in its boost phase, quasi-ballistic skipping trajectory, and ranges up to 1,500 km, made its first appearance. Developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) for coastal battery roles, it positions India among a small group of nations with operational hypersonic strike capabilities. Other homegrown systems included the Suryastra multi-calibre rocket launcher (up to 300 km range), upgraded Nag anti-tank guided missiles on tracked platforms, ATAGS and Dhanush artillery guns, and various drone and unmanned ground vehicle demonstrators.

A Deliberate Mix of Suppliers

The juxtaposition was telling. The S-400, acquired in a deal finalized despite U.S. CAATSA sanctions threats and Western pressure following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, shared the stage with deepening European and American platforms. T-90 tanks, licensed and produced in India as Bhishma variants, continue to form the backbone of armored forces, even as the Arjun undergoes iterative upgrades toward greater indigenous content. BrahMos, the supersonic cruise missile jointly developed with Russia and now exported to partners like the Philippines, represents sustained high-tech collaboration with Moscow.

The S-400 air defence system will take centre stage at this year’s Republic Day parade as part of a powerful tri-services tableau on Operation Sindoor, showcasing how India’s long‑range missile shield was used to neutralise hostile Pakistani aircraft. WATCH 👇… pic.twitter.com/q782um5WY3

— Hindustan Times (@htTweets) January 24, 2026

Meanwhile, India has diversified aggressively. France supplies Rafale fighters and Scorpene submarines; the U.S. provides P-8I aircraft, Apache helicopters, and M777 howitzers; Israel contributes Barak-8/MRSAM systems (displayed as Abhra). Domestic production now accounts for a growing share of procurement, with government figures and independent analyses showing steady progress under the “Make in India” and positive indigenization lists.

Recent SIPRI-tracked data indicate Russia’s share of Indian arms imports has declined from peaks above 60% in prior decades to around 36% in recent periods, though it remains the largest single supplier for certain critical systems. France and the U.S. have gained ground, while DRDO and private sector firms push systems like Akash (now exported), Prachand, and the hypersonic missile.

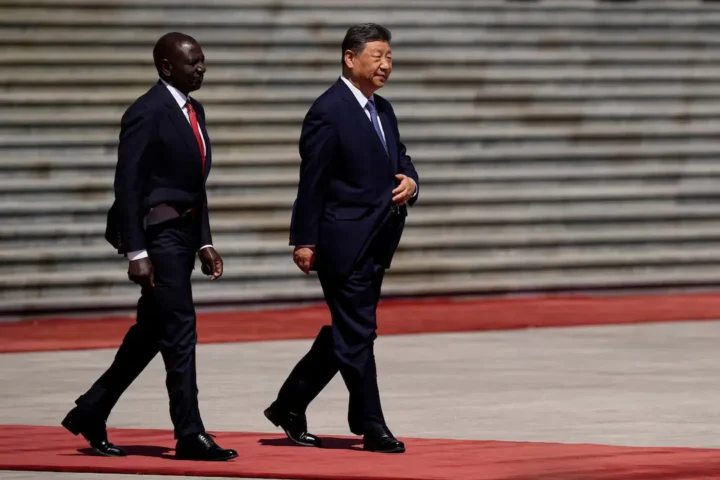

This mix reflects a policy of “multi-alignment” or strategic autonomy, Delhi’s post-Cold War evolution of non-alignment. India has not joined Western sanctions on Russia, continues discounted oil imports, and maintains defence spare parts and upgrade pipelines with Moscow. Simultaneously, it has elevated the Quad with the U.S., Japan, and Australia; signed foundational defence agreements with Washington; and pursued closer EU ties, including ongoing free-trade negotiations described by von der Leyen as potentially “the mother of all deals” creating a market of nearly 2 billion people.

EU Guests in Context

The choice of dual EU chief guests, von der Leyen, a former German defence minister focused on European strategic autonomy and resilience, and Costa, the consensus-oriented former Portuguese prime minister with multicultural roots, signals intent. Their state visit (Jan. 25-27) aligns with efforts to advance the EU-India strategic partnership in trade, technology, critical minerals, clean energy, and security cooperation. Von der Leyen emphasized “strategic partnership, dialogue and openness” and mutual resilience-building.

This occurs against a backdrop of U.S. policy shifts under a second Trump administration, renewed Russia-China alignment, and European concerns over energy security and defence industrial capacity. India’s invitation of EU leaders while prominently displaying Russian hardware and touting recent operational use of the S-400 in Operation Sindoor conveys that New Delhi will not be compelled to abandon established partners for the sake of Western alignment.

VIDEO | At the 77th Republic Day 2026 parade on Kartavya Path, the Indian Armed Forces presented a powerful Tri-services tableau titled "Operation Sindoor: Victory Through Jointness", symbolising strength, unity, and the guarding of national sovereignty through transformed… pic.twitter.com/FHdqqDaKF2

— Press Trust of India (@PTI_News) January 26, 2026

Indian officials and analysts frame this as pragmatic self-interest. Russia remains a reliable supplier for volume platforms and spares; Western and Israeli systems fill high-end gaps; indigenous programs reduce long-term vulnerabilities. The phased battle array itself emphasized “jointness” across services, a longstanding reform goal, while the Operation Sindoor tableau showcased integrated use of diverse-origin assets: French missiles, Russian air defences, Indian platforms.

Looking Ahead

The parade’s message extends beyond symbolism. For European partners seeking to reduce dependence on U.S. or Chinese supply chains and diversify defence exports, India offers a large, growing market and potential co-development partner. Recent EU-India defence dialogues have covered maritime security, counterterrorism, and cyber issues; France has deepened submarine and aircraft ties, and talks with Germany on transport aircraft and other platforms continue.

While some issues remain, they are increasingly being addressed through steady institutional learning and long-term partnerships. Technology transfer is expanding in scope and depth, and the indigenization of sophisticated systems such as engines, radars, and seekers is progressing through sustained investment and collaborative development. Continued engagement with Russia for spares and support, alongside diversification of suppliers, provides operational continuity. The prominent display of the S-400 underscores India’s ability to field and integrate world-class air defence capabilities, reflecting both technical maturity and strategic autonomy in safeguarding national airspace.

India’s defence exports are on a clear upward trajectory, driven by successful platforms such as BrahMos, growing international interest in Akash air defence systems, and the expanding portfolio of unmanned and loitering munitions. While imports remain significant, they coexist with a rapidly strengthening domestic industrial base. The hypersonic missile’s debut highlights India’s entry into an elite technological domain and forms part of a wider, carefully sequenced modernization effort that balances capability development with fiscal discipline, even as India manages complex security dynamics along its northern and western borders.

The 2026 Republic Day parade offered a window into India’s defence posture: capable of integrating Russian, American, French, Israeli, and indigenous systems; willing to host Western leaders while showcasing hardware from a sanctioned Russia; and incrementally building self-reliance without isolation. As von der Leyen and Costa observed the flypast and rolling columns, the display subtly illustrated a core tenet of Indian foreign policy, autonomy through diversification rather than exclusive alignment. In an era of intensifying great-power rivalry, such balancing acts may become more common, but few nations execute them on this scale.