Masoud Pezeshkian, at 69, has become Iran’s oldest president, an embodiment of political perseverance in a country where navigating the treacherous waters of hardline politics requires exceptional acumen. His election last Friday, however, was marked not by overwhelming support but by a striking apathy—less than half of the eligible voters turned out, and a mere quarter endorsed him.

Pezeshkian’s tenure as a moderate in a hardliner-dominated political landscape sets the stage for a presidency fraught with challenges and limited in ambition. His campaign promises, though earnest, are modest and couched within the bounds of Iran’s stringent laws and regulations. As Hassan Mohammadi, a professor at the University of Tehran, noted, Pezeshkian aims to fulfill his promises as far as the system permits, but he has no grand vision of reshaping Iran’s authoritarian theocracy or challenging the supremacy of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Among his primary goals is to alleviate some of the regime’s harsher measures, particularly those affecting women. Pezeshkian’s stance on the mandatory headscarf laws, symbolized by his campaign declaration that women are not being treated justly, signals a potential rollback of the morality police’s punitive actions. If realized, this could see millions of Iranian women casting off their headscarves in defiance, reminiscent of the protests following Mahsa Amini’s death in 2022. This anticipated pushback from hardliners might be Pezeshkian’s first significant test of power.

Recent events hint at the resistance Pezeshkian is likely to encounter. A friendly call with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan led to the abrupt closure of the Turkish Airlines office in Tehran because female staff were not adhering to Iran’s dress code. This incident underscores the persistent friction between Pezeshkian’s moderate stance and the conservative establishment’s rigid adherence to the status quo.

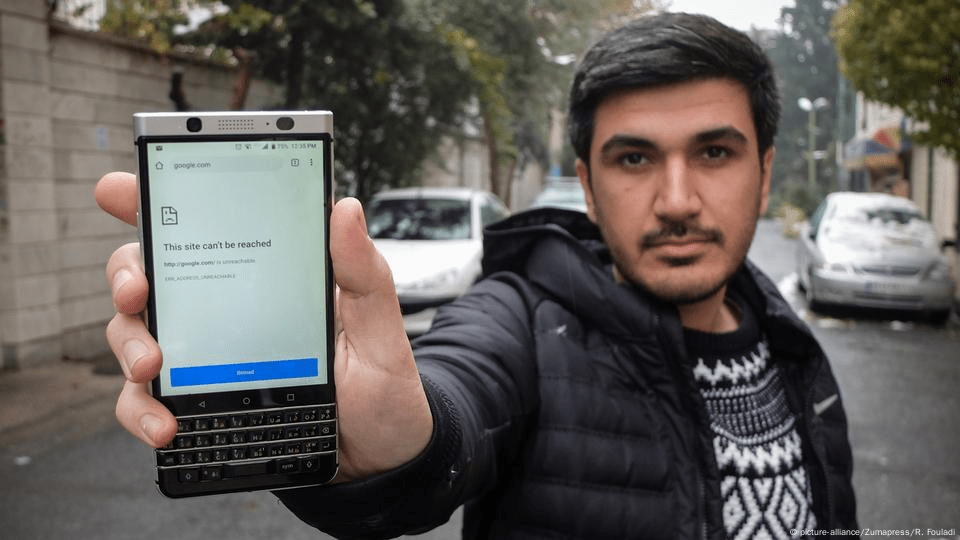

Another area where Pezeshkian promises change is internet freedom. Currently, Iran’s internet is heavily restricted, with popular social media and Western news sites banned. Pezeshkian has criticized these restrictions, pointing out that they enrich middlemen selling anti-filtering software while burdening users with high costs. However, this proposed reform will undoubtedly face staunch opposition from conservatives who fear that uncensored information could fuel further civil unrest—a reasonable concern given the multiple waves of demonstrations Iran has witnessed over the past decade.

On the international stage, Pezeshkian’s hopes for better relations with the West to alleviate sanctions will be complicated by the internal divide favoring stronger ties with Russia and China. The outcome of the upcoming U.S. presidential election could also heavily influence his foreign policy strategy, particularly if former President Donald Trump, known for his hardline stance on Iran, returns to power.

Pezeshkian’s foreign policy, particularly his unwavering support for groups like Hezbollah, aligns firmly with the regime’s long-standing positions. His letter to Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah reaffirming Iran’s support against Israel illustrates his commitment to the Supreme Leader’s directives, ensuring continuity rather than change in this contentious area.

In essence, Pezeshkian’s presidency is poised to be a delicate balancing act. While he aspires to introduce moderate reforms and improve Iran’s global standing, his efforts will be constantly checked by the entrenched power of hardliners and the overarching authority of Ayatollah Khamenei. Whether he can navigate this path without provoking a backlash that stifles his modest ambitions remains to be seen. For now, Iran watches cautiously, harboring low expectations but hoping for incremental progress under its oldest new president.