Dear readers,

The other day I was driving with my brother, who was playing D.J., when one of his song selections took me by surprise. “I thought you hated Elvis Costello,” I said accusingly and maybe a little resentfully, thinking of the decades of fruitless arguing this perception had occasioned. Charlie shrugged. “I was wrong,” he said.

Among its other benefits, voting for the 100 Best Books of the 21st Century forced us all to question our perceptions, some long held. Did I love a book out of habit, or duty? Had I outlived my objections? Had I just read something at the wrong age — or did a book not hold up? It was a great exercise, not only in revisiting favorites but also in challenging assumptions. And it turns out, being wrong is one of the best things in life. (But I’m afraid my objection to “The Dud Avocado” is set in stone.) These are books and authors I’ve reconsidered as an adult.

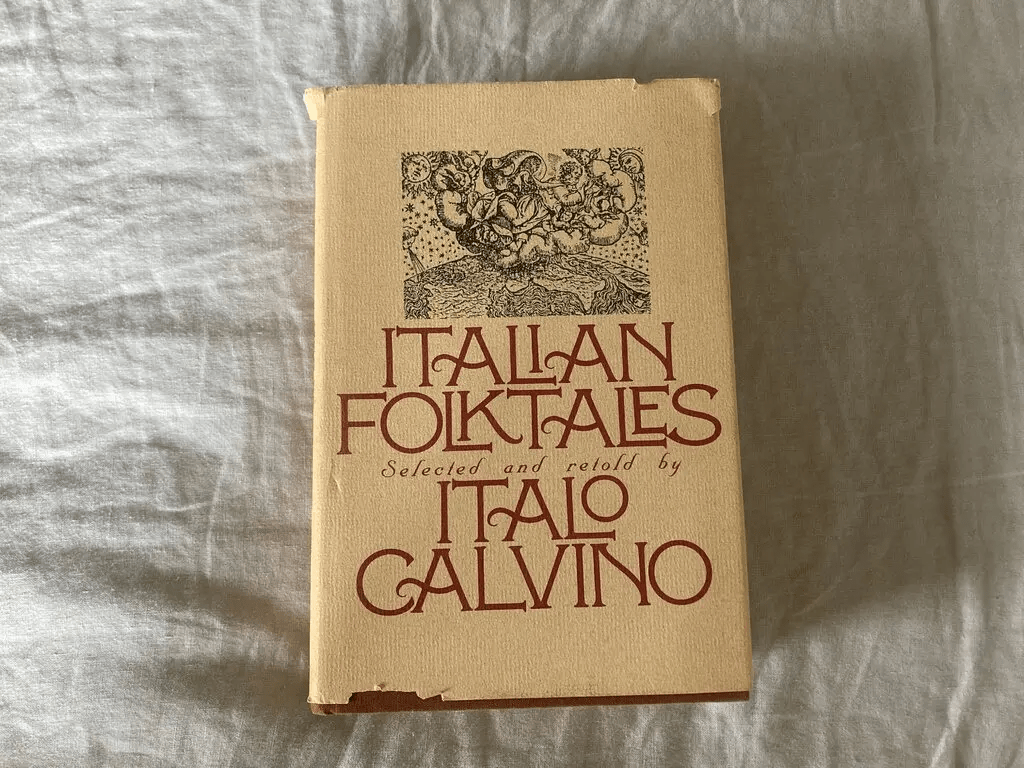

“Italian Folktales,” by Italo Calvino

Fiction, 1956

Why did I think I didn’t much like Calvino? I suspect I came to him too young, having picked up “Invisible Cities” in a storm of indiscriminate reading before college. Maybe someone I didn’t like in a freshman humanities class overpraised “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler.” Maybe I didn’t like “Italian postmodernism,” or at least liked saying that. I don’t remember the exact reason; I am sure it was stupid.

Two things changed my thinking (three if you count growing out of your early 20s). First, I read his letters and became interested by the dramatic vicissitudes of his life and career, the shifts in his philosophies, politics and style, the worlds he straddled. Then I read his “Italian Folktales.” While Calvino positioned himself as an Italian Brothers Grimm, collecting lore from all over the country, the translations and the introduction are distinctly his — and you’ll never read his other work without being aware of the thousands of years of spells and witches and herbal medicine and curses and the everyday dark magic that suffuses it. “A continuous quiver of love runs through Italian folklore,” he writes. I like “The Science of Laziness,” but my son prefers “The Three Dogs.” (Read Ursula K. Le Guin on the collection as a whole, here.)

Read if you like: “Lies and Sorcery,” by Elsa Morante; “The Uses of Enchantment,” by Bruno Bettelheim; “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” by Gabriel García Márquez.

Available from: University of Utah Archive; or seek out this spectacular work of art from the Folio Society.

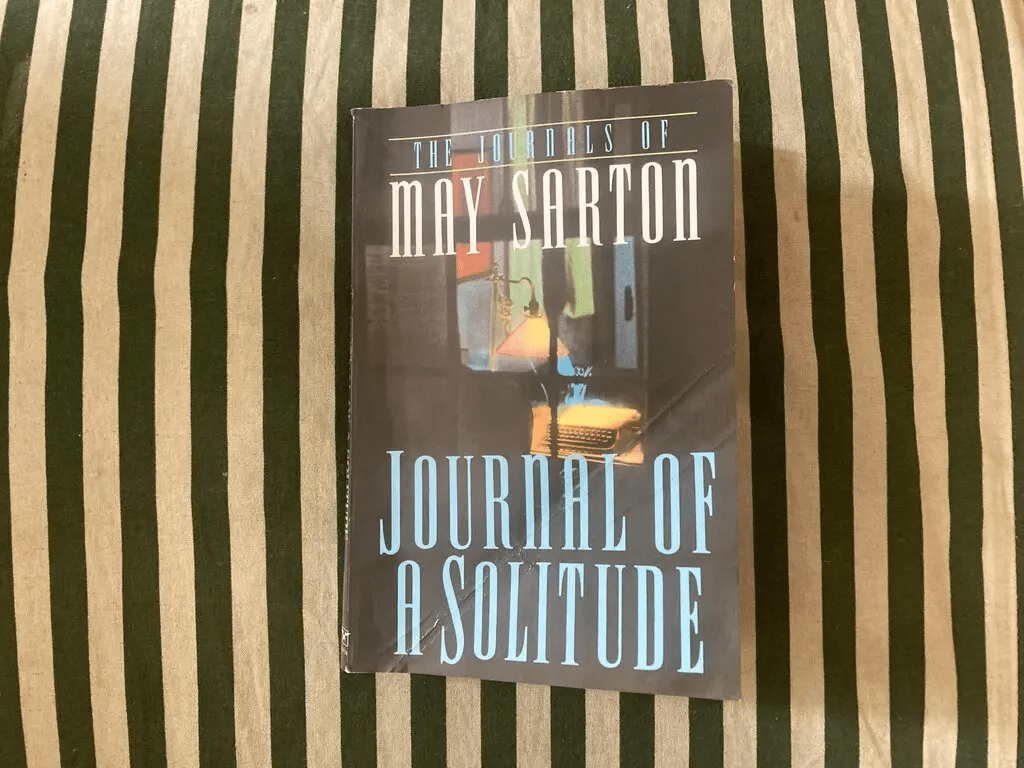

“Journal of a Solitude,” by May Sarton

Nonfiction, 1973

It was never May Sarton’s fault. I had the idea, implanted by too many friends whose taste I trust, that I would — and should — love her work. I read “The Magnificent Spinster,” and thought it was … fine. I read “Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing” and was very glad it existed and very glad I didn’t need to read it ever again. I read several books of poetry; I read Margot Peters’s scathing biography. I was always struck by her control and by moments of crystalline perfection, but Sarton’s writing inevitably left me a little cold. Then I found “Journal of a Solitude.”

This is from the first entry:

“On my desk, small pink roses. Strange how often the autumn roses look sad, fade quickly, frost-browned at the edges! But these are lovely, bright, singing pink. On the mantel, in the Japanese jar, two sprays of white lilies, recurved, maroon pollen on the stamens, and a branch of peony leaves turned a strange pinkish-brown. It is an elegant bouquet; shibui, the Japanese would call it. When I am alone the flowers are really seen; I can pay attention to them. They are felt as presences. Without them I would die. Why do I say that? Partly because they change before my eyes. They live and die in a few days; they keep me closely in touch with process, with growth, and also with dying. I am floated on their moments.”

All of those friends, I’m pleased to concede, were right, and I was wrong.

Read if you like: “Last House,” by M.F.K. Fisher; ‘In Praise of Shadows,” by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki.

Available from: A reliable library or bookseller, or direct from Norton. (I especially like this edition, if you can find it.)

Why don’t you …

- Curl up with a good, four-ply movie? Odds are, I was going to like a book called “How Directors Dress” — and I do. Yasujiro Ozu’s iconic bucket hat; Satyajit Ray’s impeccable tailoring; the pack of cigarettes rolled in the sleeve of François Truffaut’s sweater: It’s fantastic on several levels. I particularly enjoyed Lynn Yaeger’s essay on “Early Hollywood Women Directors” and “Louche,” by Rachel Tashjian.

- Covet? In this era of easy access, it can be bracing to come across something you really can’t find. (I don’t mean Birkin bags, although I suppose it’s a matter of preference.) Not long ago I was staying with a friend and came across a beautiful, unusual book: “Karen Blixen’s Flowers.” It’s a picture-heavy text featuring austere (yet lush!) arrangements, often in tureens, of wildflowers and garden blooms — apparently a passion of the writer known as Isak Dinesen. It turns out you can’t get the book for love or money, unless you have lots and lots of it to offer. But here is a lovely World of Interiors piece on the woman who recreates the arrangements in Blixen’s house, Rungstedlund; and you can see some images from the book, here. I’m contenting myself by putting flowers in tureens.

- Shod yourself? As readers of this space know, I often pick up reading material from my lobby’s giveaway table. This week, I really struck gold: “My Mother, Myself,” by Nancy Friday; “Death in the Stocks,” by Georgette Heyer; and a book by Anna Davis called “The Shoe Queen,” whose back cover describes it thus: “Davis immerses readers in the glitter and excitement of 1920s bohemian Paris — where one woman’s obsession with shoes leads her into a steamy affair that will make her question what matters most in life.”