The birth rate in South Korea has fallen so low that it is no longer just a demographic statistic—it is an existential alarm bell. With women now averaging just 0.75 births over their lifetimes, South Korea has the lowest fertility rate on Earth. This is not a minor fluctuation. It is a collapse, one that threatens to unravel the country’s social fabric, weaken its economy, and leave future generations with a crushing burden.

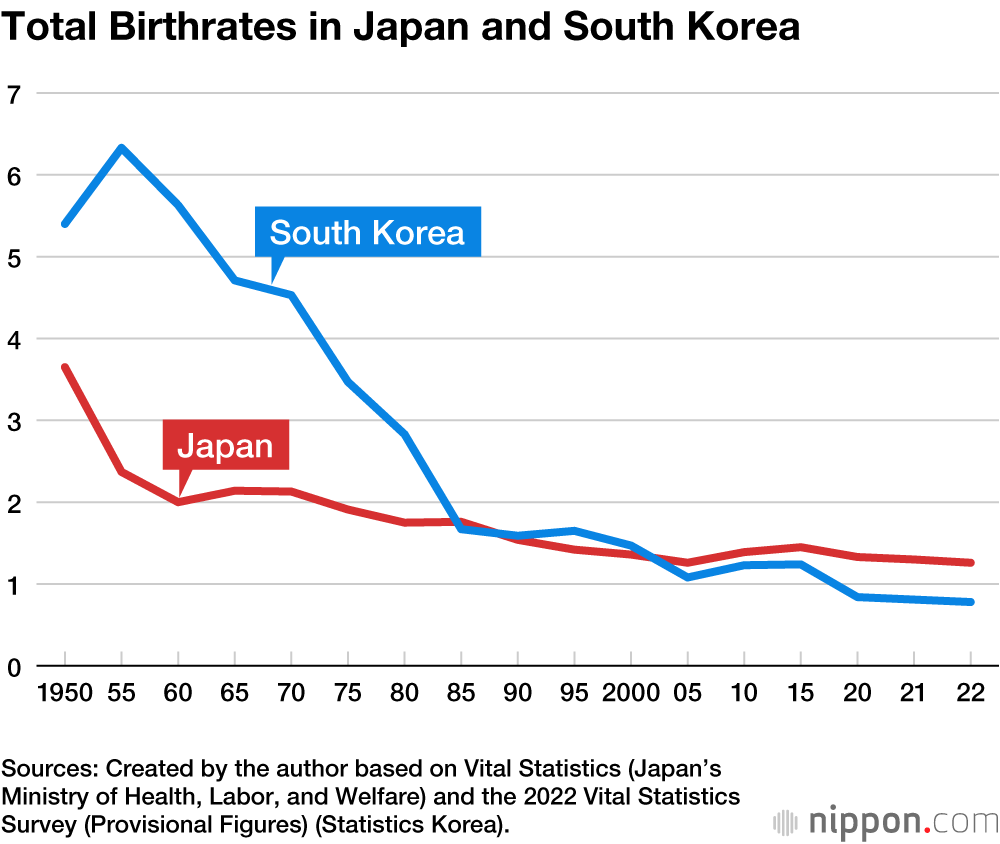

Other countries are watching closely. Across the developed world, fertility rates have slipped well below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman. The OECD average is just 1.5. Japan’s struggles are already a cautionary tale, with its aging population and shrinking workforce constraining growth and straining public finances. But South Korea’s trajectory is even more dire—and it illustrates in stark terms how cultural expectations, economic pressures, and outdated gender norms can combine to suppress family formation.

Marriage as a Gatekeeper

At the center of South Korea’s demographic dilemma is marriage. Unlike in many Western societies, where cohabitation and childbearing outside of marriage are increasingly common, fewer than 4% of South Korean births occur outside wedlock. Having children, in other words, is still tightly bound to marriage.

But marriage itself is disappearing. In 1990, more than 90% of women aged 25 to 49 were married. By 2020, that figure had dropped to 69%. Among university-educated women, the rate fell even further, from 81% to 61%. Because higher education enrollment has surged—72% of women had university degrees in 2020 compared to just 12% in 1990—the effect on marriage rates has been dramatic.

And here lies the paradox: fertility rates among married women have remained fairly stable over the decades, averaging around 1.7 children. The real decline has come from fewer women choosing to marry at all.

Education and Expectations

Why are educated South Korean women turning away from marriage? One answer lies in shifting gender dynamics colliding with unyielding traditions.

Nearly 85% of college-educated women marry men who also hold a degree. But as women now outpace men in higher education, the pool of “acceptable” partners shrinks. Many women are unwilling to “marry down,” and many men remain uncomfortable with partners who earn more or have better career prospects.

The bigger problem, however, is what awaits women after marriage. Household labor in South Korea remains deeply unbalanced. Women aged 15 to 64 spend an average of 215 minutes per day on unpaid domestic work, compared to just 49 minutes for men. More children mean more work—almost all of it falling to mothers.

On top of that, workplace culture continues to punish women who try to combine careers and family. Nearly two-thirds of South Koreans believe that children suffer if their mothers work outside the home, a figure twice as high as in the United States. Employers often act on this assumption, sidelining women once they become mothers. For many ambitious, educated women, the trade-off is stark: family or career, but not both.

The Financial Mountain

Even for couples who want to marry and have children, the costs can be prohibitive. Social norms dictate that couples should buy a home before marriage, but Seoul’s real-estate market is among the most expensive in the world. Without substantial help from parents, young people are priced out.

Then comes the education arms race. Admission to South Korea’s elite universities is so fiercely competitive that parents often spend lavishly on private tutoring to give their children an edge. Between 2007 and 2022, household spending on tutoring grew nearly 5% per year in Seoul. For many families, the financial stress of raising even one child feels overwhelming.

Policy Options, and Their Limits

It would be tempting to see this crisis as inevitable, the product of modern prosperity and individual choice. But structural barriers are central to South Korea’s fertility collapse—and that means policy can make a difference.

Several measures stand out. Affordable housing for newlyweds would remove a major obstacle to marriage. Subsidized childcare and expanded parental leave could ease the early years of childrearing. Family-related spending in South Korea remains among the lowest in the OECD, suggesting plenty of room to scale up.

But money alone is not enough. The bigger challenge is dismantling entrenched gender norms. Policies that encourage fathers to take parental leave, share household labor, and be more present in childcare are crucial. So are labor-market reforms that ensure women are not penalized for motherhood. Greater workplace flexibility could allow parents to balance careers and family life without feeling forced to choose one over the other.

Perhaps most difficult of all will be loosening the grip of Confucian tradition, which still insists that children must be born within marriage. Societies elsewhere have managed to accept diverse family structures—cohabiting couples, single parents, same-sex parents. South Korea, by clinging to rigid norms, is narrowing the pathways through which its citizens can choose to raise families.

The Global Lesson

South Korea’s predicament is extreme, but it is not unique. Fertility rates across Europe, East Asia, and North America are well below replacement. Everywhere, young people weigh the same questions: Can I afford a family? Will I have to give up my career? Will my partner carry an equal share of the load?

If those questions are answered with doubt, hesitation, or resignation, birth rates fall. South Korea is simply the leading edge of a broader trend.

Avoiding Collapse

Raising fertility rates will not be easy, and even the most ambitious reforms are unlikely to restore them to replacement levels. But that does not mean policymakers should shrug. If South Korea can lift its birth rate from 0.75 to even 1.2—the level of Japan—it would make a profound difference for the sustainability of its economy and society.

The alternative is grim: a shrinking workforce, soaring dependency ratios, and a country that ages into decline.

South Korea’s crisis is a warning. It tells us that when social norms and economic structures clash with women’s aspirations, fertility can collapse. But it also tells us that change is possible. With bold reforms—economic, cultural, and institutional—South Korea can move away from demographic freefall. The question is whether leaders have the courage to act before it is too late.