Australia, a treaty ally of the United States, published a comprehensive National Defence Strategy (NDS) in April 2024. The NDS delineates the country’s plans to expand its role in Indo-Pacific security, emphasizing multilateral collaboration, the development of a proactive and integrated military, and substantial increases to the defense budget. The strategy represents a recalibration of Australia’s defense posture in response to the growing assertiveness of the Chinese military, competition between China and the United States, and other rising security risks.

What is Australia’s new strategy for national defense?

A strategy of denial. Although deterring attacks on the Australian homeland has always been one of the country’s defense priorities—alongside shaping the regional environment and responding to threats as necessary—deterrence has now become Australia’s top priority. That reordering of priorities indicates that Canberra is moving toward a more proactive conflict prevention approach, sending a stronger warning signal to China meant to ward off attempted coercion or incursion.

Australia, which is over 2,400 miles from China, is less geographically vulnerable to direct military attack from China than many of its partners in the Indo-Pacific, such as Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan. It has, however, signaled heightened awareness of the potential threats China poses to its interests. As the NDS states, improved technology has overturned Australia’s long-standing geographical advantage. China’s growing missile arsenal, increased gray zone aggression, and intimidation of other U.S. partners in the Pacific waterways are particularly concerning. Those concerns are not merely theoretical: Australia has been a victim of Chinese economic coercion, when China restricted various Australian imports between April 2020 and May 2024 following Australia’s early call for an international investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

Physical separation from China will not spare Australia from the broader effects of great power confrontation, so Australia intends to deny China any opportunity to threaten its security by making the prospect too dangerous and costly to consider. To that end, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) intends to better integrate and modernize itself and evaluate strategic risks before they materialize.

Indo-Pacific partnerships. The defense strategy strives to preserve the current favorable regional security balance, bolster the rules-based international order, and protect Australia’s economic connection to the rest of the world. Perhaps most emphasized, though, is Canberra’s effort to contribute to the collective security of the Indo-Pacific. Discussing partnerships with Japan and the Philippines, Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles has emphasized that “the defense of Australia doesn’t mean much unless we see the collective security of the region.” As security dynamics change, Australia is not just leaning forward on defense for homeland security reasons, but also because it sees a role for itself in protecting its neighbors and the future stability of the Indo-Pacific.

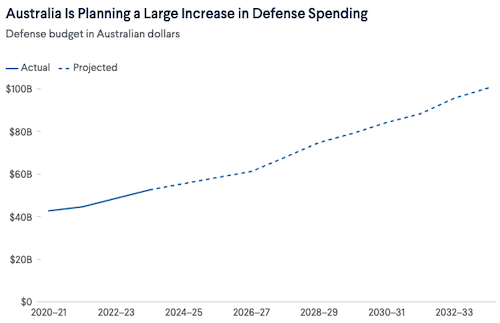

A generational investment. The coming decades will see Canberra pursue massive defense budget increases, including a near doubling of defense spending within ten years—from roughly $35 billion USD in 2024 to over $66 billion by 2033. The Australian government plans to ramp up military equipment production and procurement, construct new military bases on its northern coast, and boost innovation and production within the defense sector. That relatively rapid budget hike points to the urgency of the NDS as a whole; to accelerate defense procurement, for example, the country plans to change requirements for the introduction of certain new weapons systems, prioritizing production speed above other criteria.

What does Australia’s new plan mean for cooperation with the United States and its allies?

The NDS emphasizes the importance of AUKUS—Australia’s trilateral defense technology and equipment-sharing agreement with the United States and the United Kingdom (UK). Namely, the strategy document includes a twenty-plus-year plan for the Australian Royal Navy to train with, purchase, and ultimately build conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines—technology that the United States previously only shared with the United Kingdom. Australia will be the second U.S. ally to gain access to the technology themselves. Advanced underwater capabilities are important to deterring Chinese aggression in the Pacific, and the nuclear-powered submarines promised to Australia through AUKUS can enhance deterrence by complicating China’s targeting. However, the effort could be imperiled by shortfalls in Australia’s shipbuilding capacity, and some experts argue that the United States should prioritize building more nuclear submarines for its own navy over assisting the Australians.

Beyond AUKUS, Australia is otherwise deeply integrated in the United States’ emerging “lattice” of allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific, a network of countries working to deepen bilateral ties with one another and foster relationships through a network of minilateral groupings to address precise goals. One such group is the Quad, a security-focused partnership made up of the United States, Australia, India, and Japan. In 2023, Australia also joined the United States, Japan, and the Philippines for military drills intended to counter China’s intimidation of the Philippines in the tumultuous South China Sea. Those drills were intended to signal support for a vulnerable U.S. ally and provided another opportunity for Canberra to show its increasing willingness to assume a leadership role in the region.

Although Australia will prioritize security cooperation closer to its shores, it will make what it calls “calibrated contributions” to security further afield where appropriate and necessary. Australia is notably an existing member of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing network (with the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK) and a regional partner of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

What does Australia’s plan suggest about the broader security environment in the Indo-Pacific?

Australia’s new NDS offers an insight into a larger regional trend. Japan is several years into its own decade-long national defense buildup, while Taiwan has nearly doubled its defense spending over the past eight years and continues to invest in its military capabilities. Indonesia, historically closer to China, has shown signs of openness to a defense cooperation agreement with Australia that would allow for the growth of the Indonesian defense sector. The United States’ latticework of Pacific allies is coalescing to reinforce deterrence against Chinese aggression beyond a level possible under the siloed approach of the past, and Australia is preparing itself for a prominent role in that effort.