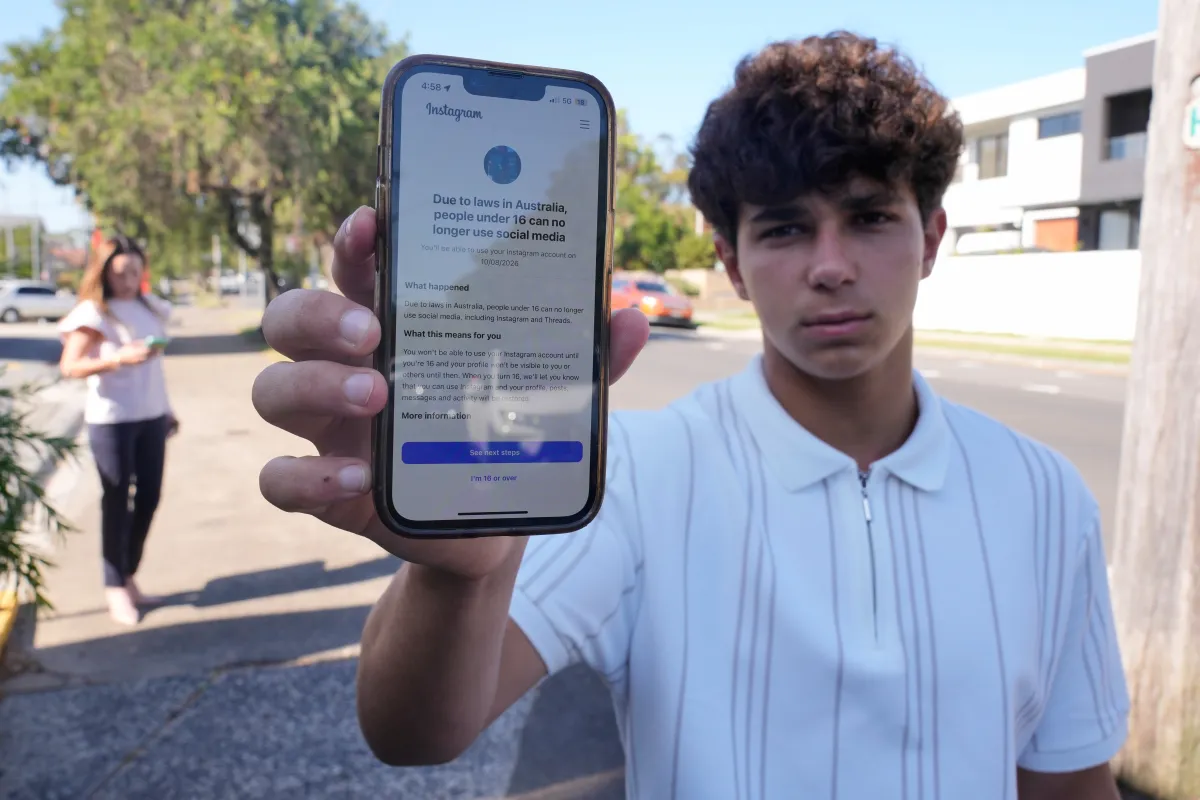

Australia has just crossed a threshold that many governments have considered but few have dared to enact. As of this week, anyone under 16 is officially barred from creating accounts on major social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok and Facebook. It is a seismic change not only for Australian teenagers but also for parents, technology companies and legislators around the globe who have been tracking the policy with intense interest.

This is more than a national rule change. It is the world’s first large-scale attempt to disconnect children from mainstream social media entirely. Whether it succeeds, stumbles, or evolves into something different, experts agree: it will be studied everywhere.

Why Australia Jumped First

The ban is the product of years of mounting concern. Inquiries, royal commissions and parliamentary debates have repeatedly raised alarm about algorithmic feeds, targeted content and online environments that amplify risks for children — from addictive design to exposure to sexualised material and violent content.

Lawmakers insist this is not an anti-technology crusade but a public health intervention. They speak of social media like a substance that is not inherently evil, but potentially damaging in the wrong dosages and at the wrong developmental stages. Still, enforcement will likely be the test. Age verification technology remains underdeveloped and children have a long history of circumventing digital rules — from fake dates of birth to borrowed devices.

The Copycats and the Curious

If Australia is the world’s experiment lab, other countries are waiting for results but not necessarily waiting to act.

In Europe, the momentum is unmistakable. The European Parliament formally called for a ban for under-16s in November, with Commission President Ursula von der Leyen explicitly citing Australia as her case study. She described social media ecosystems as “algorithms that prey on children’s vulnerabilities” and argued that families are drowning in content they cannot realistically control.

France is considering its own age-based prohibitions — a ban for under-15s and even a curfew for older teens from 10pm to 8am. It could become illegal not just for platforms to allow children online after hours, but also for parents to neglect digital protections. Among 43 recommendations from a 2025 inquiry was a proposed offence of “digital negligence,” signalling a shift from voluntary guidance to legal accountability.

Spain is tightening rules too, lifting the standard minimum age from 14 to 16 unless parents opt in. Germany also technically requires under-16s to obtain parental consent for accounts, though without meaningful verification, the rule currently exists more on paper than in practice.

Scandinavia, often a pioneer in child welfare policy, is moving in parallel but with nuances. Norway plans restrictions for under-15s, emphasising that any law must balance rights: freedom of expression, access to information and the simple ability to socialise online. Denmark has declared it will pursue a ban similar to Australia’s, but parents will be able to override it for 13- and 14-year-olds. The timeline is uncertain, but Denmark has one advantage Australia does not — a national digital ID system that could make age checks technologically feasible.

Asia’s Slow but Steady Regulation

Across Asia, the approach varies but the trend is unmistakable: more control, earlier intervention.

Malaysia will ban social media accounts for those under 16 beginning in 2026. Before that, in 2025, all large platforms will need licences to operate, and must implement age verification systems and safety controls.

Pakistan and India are also focusing on exposure to harmful content but opting for a different toolkit: mandated parental consent, proof of age, and clearer obligations for platforms to filter and moderate.

New Zealand may be the closest philosophical neighbour to Australia. It has already announced its intention to legislate similarly, but only after a parliamentary committee delivers its recommendations in early 2026.

Alternatives and Rebellions

Not everyone is following Australia’s hardline stance.

South Korea rejected a national ban, though it will prohibit mobile phones in classrooms beginning in 2026 — a move aimed at distraction rather than outright digital detox.

Japan has offered one of the most intriguing counter-models. The city of Toyoake imposed a universal screen-time limit: no more than two hours a day on devices for all ages. The mayor argues that if adults do not model restraint, children will simply disregard rules. The ordinance is not enforceable, but surveys show 40% of residents changed their habits and 10% cut smartphone use. It is an argument rooted less in punishment and more in cultural expectation.

The American Flashpoint

While many countries are aligned in their concerns, the United States has erupted in opposition to Australia’s approach. Technology giants and media organisations have framed the ban as hostile to American business interests and as a precedent that could inspire similar controls elsewhere.

President Donald Trump has promised to resist what he describes as an attack on US companies. Australia’s eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman-Grant was summoned before Congress, where she faced accusations from Republican Jim Jordan that Australian rules “threaten speech of American citizens.” Inman-Grant rejected this argument and maintained that the regulations apply to platforms operating in Australia regardless of national ownership.

No Universal Formula — Yet

Across all jurisdictions, one truth dominates: there is no consensus on when a child is ready for social media, or whether age alone even captures readiness. Some nations are leaning toward firm prohibition, others towards parental empowerment, and others towards structural regulation of platform design.

Australia now finds itself in the role of global test subject — not because it is the only country worried about online harms, but because it is the first to act with sweeping force. If teenagers evade the rules en masse, if platforms fail to verify, or if new underground networks emerge, critics will have material ready. If mental health indicators or safety outcomes improve, imitators will multiply.

Either way, the world is watching not just to see if Australia can keep children off social media, but to answer an even bigger question: can any nation reassert democratic control over a digital realm built to resist it?