In the labyrinthine corridors of South Asian geopolitics, India stands at a precipice with the sudden exit of Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. The drama unfolded not in the bustling capital of New Delhi, but in the quieter confines of the Hindon airbase in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. This choice of locale for Hasina’s arrival speaks volumes about India’s cautious distance from the ousted Bangladesh leader. Yet, as New Delhi navigates this diplomatic minefield, one pressing question looms: Can India avoid the specter of an anti-India backlash in Bangladesh?

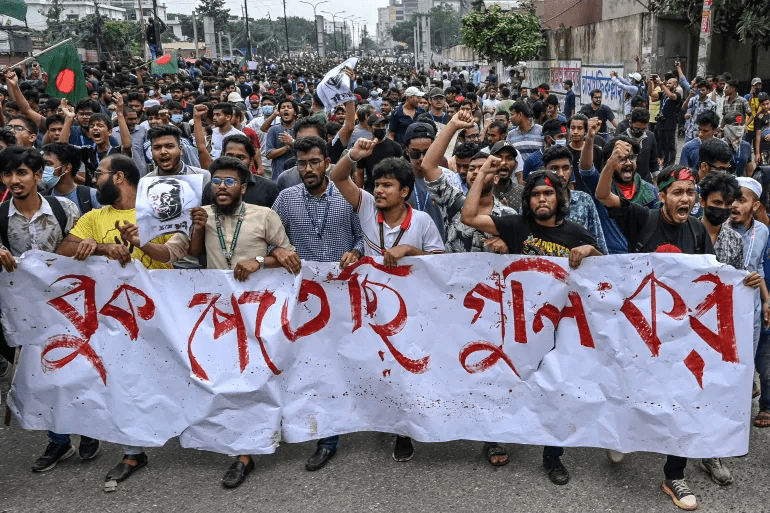

Sheikh Hasina’s fall has rippled through Bangladesh’s political landscape, potentially empowering her adversaries—the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. Both factions harbor little goodwill towards India, painting New Delhi’s predicament in stark, uncertain terms. The perception among many Bangladeshis that India’s alliance with their nation was merely an endorsement of Hasina’s regime, rather than a commitment to the country’s democratic ethos, further complicates matters.

This isn’t an isolated incident in India’s regional diplomacy. The subcontinent has seen similar shifts in Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Nepal, each time leaving India scrambling to rebuild trust and influence. Now, with the winds of change blowing through Dhaka, India must pivot swiftly to engage with democratic and secular elements within the Bangladeshi opposition.

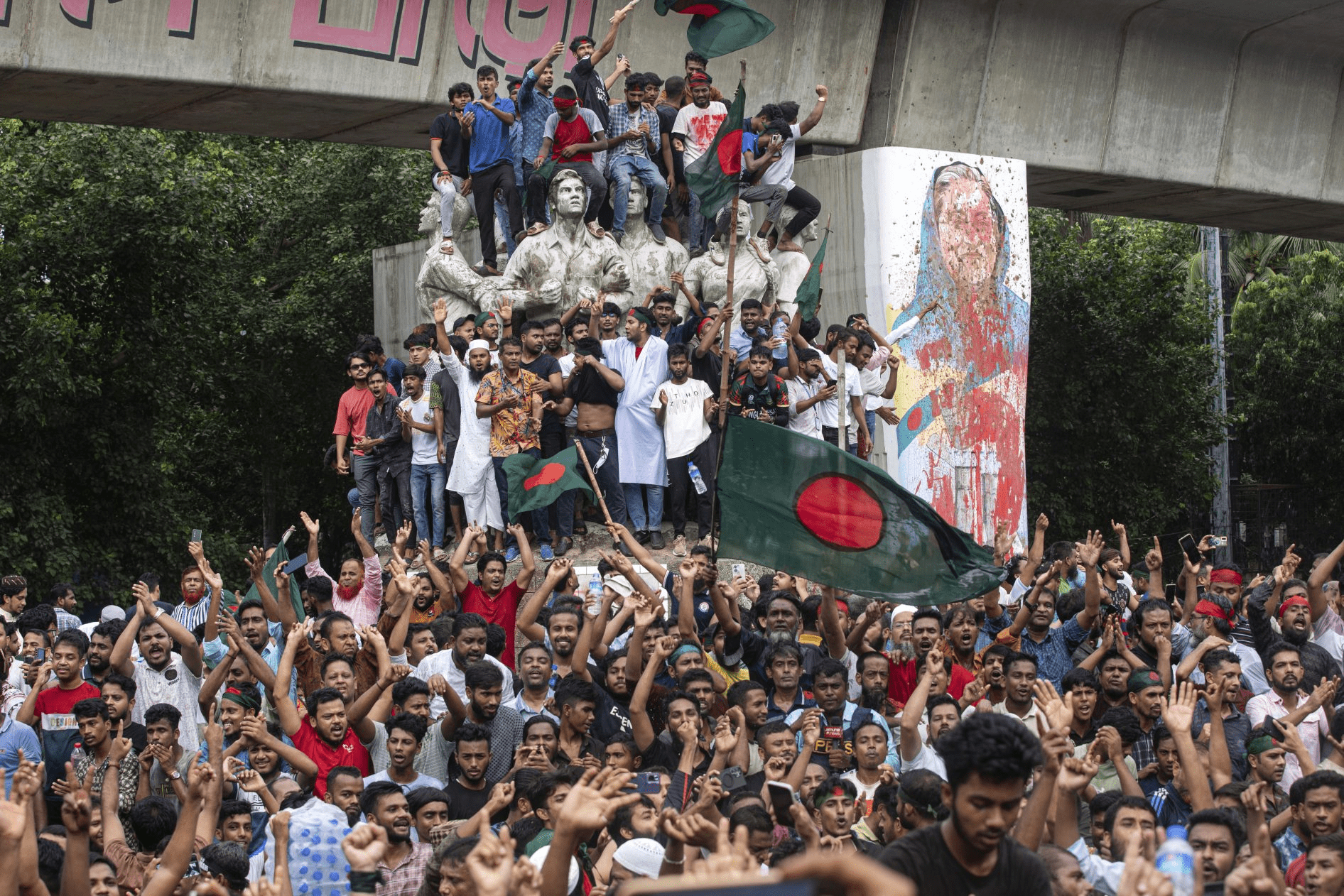

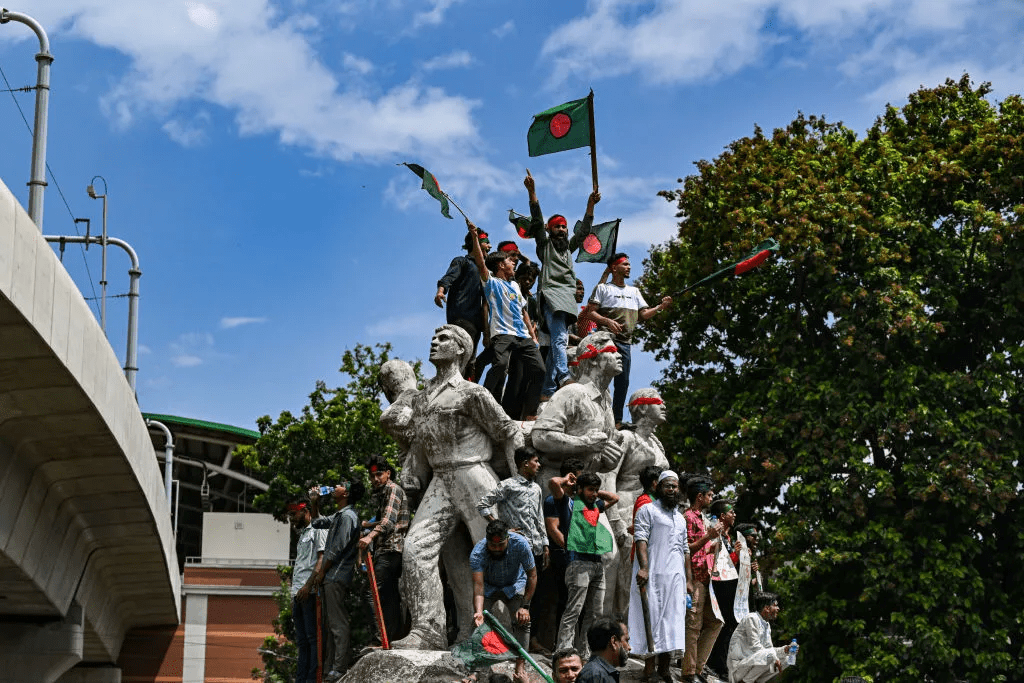

New Delhi’s earlier hands-off approach, underpinned by a belief in Hasina’s capacity to quell unrest, now appears miscalculated. The Indian foreign ministry’s statement on July 19, declaring the turmoil in Bangladesh as an “internal matter,” seemed more of an evasionary stance. As violence escalated, many in Bangladesh hoped for a more empathetic Indian response, at least a call for peace, if not an outright condemnation of the brutality meted out to protesting students.

However, India’s silence is partly understandable. A vocal stance might have strained ties with Hasina’s government, potentially pushing Dhaka closer to Beijing. The specter of China’s growing influence in South Asia is a persistent concern for New Delhi. Beijing’s strategic encroachments following regime changes in Sri Lanka and the Maldives serve as cautionary tales. A similar shift in Bangladesh could bolster China’s foothold, undermining India’s strategic interests.

The future of many Indo-Bangladesh projects also now hangs in a delicate balance following Sheikh Hasina’s departure, given her status as India’s closest geopolitical ally in the region. Under her leadership, India and Bangladesh forged strong economic and counter-terrorism partnerships, exemplified by ambitious connectivity initiatives such as the Akhaura-Agartala cross-border rail link, the Khulna-Mongla Port rail line, and the Maitree Super Thermal Power Project. These projects, alongside the India-Bangladesh Friendship Pipeline, were set to significantly link the two economies. Hasina’s government also saw the resolution of long-standing issues over territory and water-sharing, marking a period of unprecedented cooperation. However, with the current political uncertainty, the continuation and success of these projects depend on India’s ability to establish new, robust relationships with the emerging Bangladeshi leadership and ensure that the mutual benefits of these initiatives are recognized and upheld.

Furthermore, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) is not a dormant player in this scenario. Reports of its deep infiltration into Bangladesh’s political sphere, especially within Jamaat-e-Islami, and the recent desecration of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s statue signal a disturbing resurgence of pro-Pakistan sentiment. This resurgence not only threatens Bangladesh’s secular fabric but also portends increased persecution of the country’s 13 million Hindus—a scenario that could reverberate across the border, compelling India to intervene on humanitarian grounds.

India’s strategic calculus is fraught with challenges. The emergence of an Islamist-leaning government in Dhaka, with possible pro-Pakistan and pro-China inclinations, poses a dire security risk. Historical precedents from 2001-2006, when BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami ruled Bangladesh, illustrate the dangers. The period saw the entrenchment of Islamist extremism, often with covert support from Pakistan’s intelligence network, spilling over into India’s own territories.

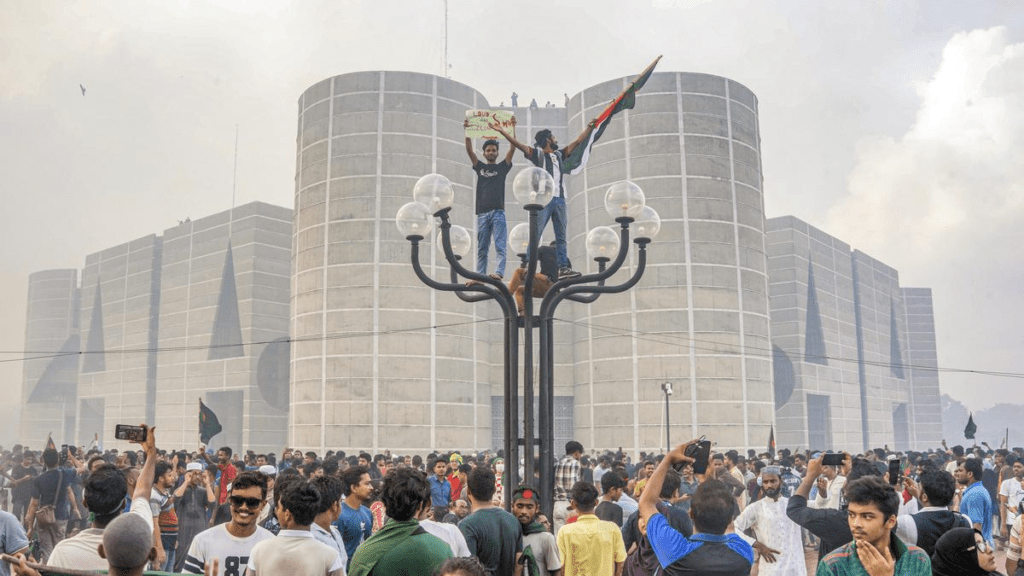

As Bangladesh teeters on the edge of another political transformation, the role of the military cannot be understated. Army chief Waker-Uz-Zaman’s sudden assertion of control hints at a significant, albeit surprising, military influence in the transition. His proximity to Hasina, through familial ties, adds another layer of intrigue to an already convoluted scenario.

India’s diplomatic arsenal must now deploy rapidly and effectively. Building alliances beyond the Awami League, fostering goodwill among ordinary Bangladeshis, and countering the influence of hostile powers will require deft maneuvering. The Indian government’s current strategy appears reactive, a symptom of its over-reliance on Hasina’s regime. A broader, more inclusive engagement with Bangladesh’s diverse political spectrum is imperative.

The formation of a credible interim government in Dhaka will be a critical juncture. Whether the military dictates terms or a more democratic structure prevails, India’s foreign policy towards Bangladesh must adapt swiftly. The stakes are high, and the path forward is fraught with uncertainty. In this unfolding saga, India’s ability to maintain regional stability and its own security interests will be tested like never before.