Kenya’s much-hyped zero‑tariff trade deal with China has quietly slipped into limbo, exposing how Beijing’s promises now often move faster than its paperwork, and how African partners are warier after a decade of debt‑fuelled mega‑projects that stalled or soured. The paralysis around the pact mirrors a broader pattern, from Kenya’s own incomplete railway to canceled coal plants and renegotiated loans across the continent, where China’s grand narratives of “win‑win” have been undercut by legal challenges, public backlash, and shrinking Chinese appetite for risk.

A deal born of anxiety

The zero‑tariff deal was supposed to be Kenya’s insurance policy for a far more frightening shock: the end of preferential access to the United States under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). When AGOA finally expired in late 2025, the Kenyan government framed a reciprocal agreement with Beijing as a lifeline for tea, coffee, avocados and other farm exports suddenly facing new barriers in their biggest rich‑country market.

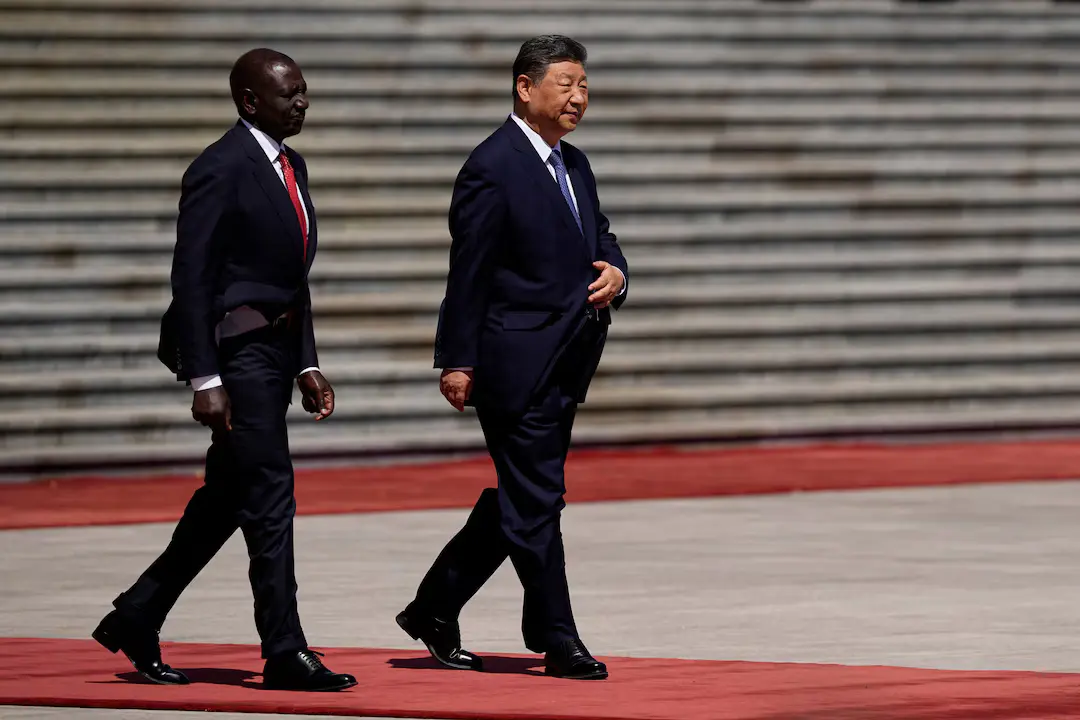

President William Ruto announced in August 2025 that China had agreed “in principle” to remove all tariffs on key Kenyan agricultural products, and Chinese ambassador Guo Haiyan publicly pledged to fast‑track implementation. The choreography looked familiar: soaring language about “win‑win cooperation,” glowing headlines about access to 1.4 billion Chinese consumers, and a promise that the formalities would be wrapped up in a matter of months.

Jitters in Nairobi, silence in Beijing

Those months came and went. The legal instruments needed to translate political promises into binding market access never materialised, and exporters who had reoriented business plans around China’s market watched the calendar with growing unease. Trade officials in Nairobi continued to talk up the deal, but the talks themselves slowed, and no clear timetable has been made public.

For Kenyan producers, the timing could hardly be worse. The country’s textile and apparel exporters, who had flourished under AGOA, now face higher costs and uncertainty in the US, while the Chinese option that was meant to cushion the blow remains stuck in negotiation. Business groups warn that jobs in Export Processing Zones hang on whether the deal is concluded soon, yet every statement from officials is still couched in vague assurances rather than concrete dates.

An unbalanced relationship in numbers

Even if the zero‑tariff pact is eventually signed, it will sit on top of a relationship that is dramatically skewed in China’s favour. In 2023, Kenya imported roughly 459 billion shillings (about 4.66 billion dollars) worth of Chinese goods, while exporting products worth only around 29 billion shillings to China. That imbalance is precisely why Nairobi resisted a broader free trade agreement under an earlier East African Community–China proposal, fearing a flood of cheap Chinese manufactures that local industry could not match.

The current plan is deliberately narrow: a focus on agricultural exports that might claw back a sliver of the deficit without throwing the Kenyan market open to all Chinese goods. Yet the very narrowness of the offer may also explain why it has slipped down Beijing’s priority list, at a time when Chinese officials are more focused on safeguarding existing loans than writing new cheques or opening sensitive sectors.

From flagship projects to stalled assets

The stasis around the trade deal cannot be separated from the troubled legacy of Chinese infrastructure finance in Kenya. The Standard Gauge Railway from Mombasa to Nairobi was once the flagship of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in East Africa; today it is a loss‑making line whose second phase to Uganda has never been built and whose original contract was declared illegal by Kenyan courts. China has quietly pulled back from funding the extension, and Kenya’s debt repayments on Chinese infrastructure loans have more than doubled in recent years, consuming a large share of foreign debt service.

Other emblematic projects have simply died. A coal‑fired power plant near Lamu, awarded to Chinese companies and billed as a pillar of Kenya’s energy future, was cancelled in 2020 after a fierce environmental campaign and concerns about its impact on a UNESCO World Heritage site. Across Africa, similar stories abound: a 3.2‑billion‑dollar railway contract in Kenya voided by judges, a 236‑million‑dollar traffic system scrapped in Ghana, and a six‑billion‑dollar mining deal under review in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

China’s retreat and Africa’s recalculation

These reversals are part of a broader retrenchment. Analysts tracking Chinese finance speak of a “great retreat” from Africa, driven by debt sustainability worries in countries like Zambia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, as well as tighter capital controls inside China. New large‑scale infrastructure lending has slowed sharply, and much of Beijing’s bandwidth is now consumed by complex, drawn‑out restructuring talks, where African governments push back against opaque terms and collateral clauses that critics say erode sovereignty.

For African capitals, including Nairobi, the political calculus has changed. Whereas Chinese money once appeared plentiful and unconditional, it is now associated with unfinished projects, contested contracts, and domestic backlash over debt. Kenya has sought loan restructuring and fresh support to complete stalled BRI projects, even as it courts Western and Gulf investors and leans more heavily on regional platforms like the African Continental Free Trade Area to diversify away from any single external patron.

A stalled deal as symptom, not exception

In that context, the frozen zero‑tariff pact reads less like a surprising glitch and more like a symptom of a relationship that is being renegotiated on both sides. Beijing is more cautious about extending preferences or new credit where repayment risks are high, while Nairobi is under pressure from its own courts, civil society, and overstretched budget to avoid repeating the mistakes of the last decade’s BRI binge.

For Kenyan exporters who took the government at its word, the distinction is academic: they are caught in the gap between political theatre and policy delivery. But the stalled deal also signals something larger—the end of an era in which China’s economic statecraft in Africa was defined by speed and spectacle, and the beginning of a slower, more contested phase in which every new agreement, even one as modest as cutting tariffs on tea and avocados, has to fight its way through accumulated debt, legal scrutiny, and mistrust on both sides.