Iran is in the midst of its largest anti‑government uprising since 2019, driven by economic collapse, anger at clerical rule, and fatigue with the costs of Tehran’s regional adventurism. At the same time, the Islamic Republic is under pressure over its nuclear program and its role in a tense regional landscape stretching from Lebanon and Gaza to the Red Sea.

The new wave of protests

A nationwide protest movement that began in late 2025 over prices and wages has morphed into direct challenges to the Islamic Republic itself. Demonstrations surged again on 8 January 2026 after a call to action by exiled crown prince Reza Pahlavi, prompting large crowds and night‑time chants in Tehran and other cities.

- Protesters are chanting against Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and, unusually, in favor of the former monarchy and Pahlavi’s return.

- Security forces have responded with live fire, mass arrests, and forced televised “confessions,” with rights groups reporting dozens killed and thousands detained so far.

What is driving the unrest

The immediate trigger is economic, but grievances cut across nearly every aspect of life in Iran.

- Years of sanctions, mismanagement, and corruption have produced high inflation, a weak currency, and rising unemployment, hitting traders, pensioners, and workers in bazaars and commercial hubs.

- Many protesters denounce the regime’s spending on armed groups abroad with slogans like “Not Gaza, not Lebanon, my life for Iran,” reflecting anger that foreign adventures are prioritized over domestic welfare.

Generational frustration is central: students and young Iranians, including “Gen Z,” are at the forefront, arguing that the system has “taken our future hostage” and that piecemeal reforms are meaningless.

How the state is responding

The state is treating the unrest as both a security and political threat.

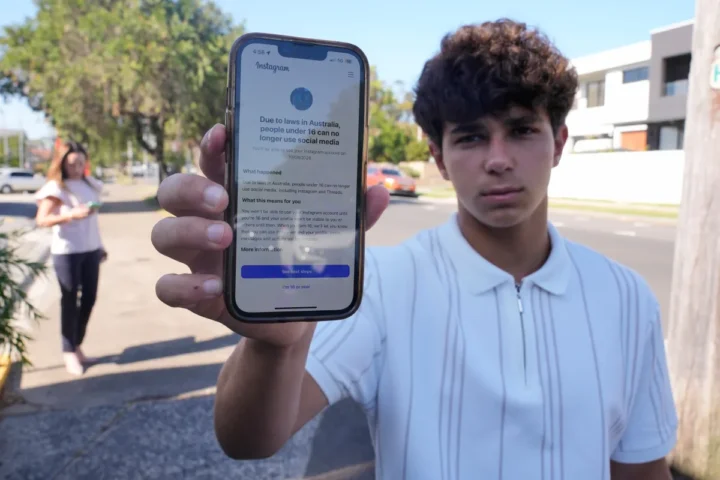

- Authorities have severely restricted internet and phone services in multiple cities, aiming to disrupt mobilization and the circulation of videos of the protests.

- Security forces and plainclothes units are raiding hospitals, universities, and protest hotspots, while state TV frames demonstrators as “terrorist agents” linked to the United States and Israel.

President Masoud Pezeshkian has tried to strike a more conciliatory tone, recognizing the constitutional right to peaceful protest and talking about meeting protest representatives, but he does not control the security apparatus, which answers to Khamenei. This split highlights a familiar pattern in Iran where elected institutions absorb public anger while unelected centers of power manage repression.

Nuclear file and external pressure

In the background, Iran remains locked in a standoff over its nuclear program with the United States and European powers.

- Talks that resumed in 2025 sought deep cuts to Iran’s enrichment, intrusive inspections, and curbs on support to regional proxies in exchange for sanctions relief and access to frozen assets.

- Negotiations have been difficult and inconclusive, with Washington pressing for dismantlement of high‑level enrichment and Tehran insisting on retaining some enrichment as a sovereign right.

The unresolved nuclear issue sustains sanctions that worsen Iran’s economic crisis, which in turn fuels domestic unrest, creating a feedback loop between diplomacy and street politics.

Iran in a tense regional theatre

The protests unfold as Iran navigates a bruised but still assertive regional role.

- After a short but intense war with Israel, Iran’s network of partners from Hezbollah in Lebanon to groups in Yemen and Gaza has absorbed significant military damage, weakening elements of its deterrence.

- Israel is preparing operational options against Hezbollah, and Gulf states, sensing Iranian vulnerability, are testing the limits of Tehran’s influence in maritime and energy disputes.

Regional and Western actors worry that a cornered Iranian leadership could respond to internal unrest by doubling down externally—through missile tests, proxy attacks, or nuclear escalation—as a way to project strength. At the same time, Iran’s need for Russian support in Ukraine‑related arms deals and for Chinese energy purchases shapes how far it can go without jeopardizing key partnerships.

Why this moment matters

The current crisis is less a single uprising than an accumulation of unresolved shocks: the 2019 fuel protests, the 2022 Mahsa Amini movement, and now a broad‑based revolt over dignity, livelihoods, and political voice. Protesters have blurred the line between economic and political demands, making it harder for the system to buy calm with short‑term concessions.

Whether this becomes a turning point depends on three variables: the cohesion of the security forces, the ability of disparate opposition figures inside and outside Iran to coordinate, and how external pressure over the nuclear and regional files interacts with the regime’s survival instinct. For now, Iran sits at the intersection of internal legitimacy crisis and regional volatility, and decisions taken in Tehran will ripple from the streets of its commercial hubs to frontlines in Lebanon, Gaza, and beyond.