In the gilded chambers of London’s high finance, behind the oak-paneled offices of legal firms and plush drawing rooms of elite estate agents, a quiet but insidious industry thrives. It does not build, invent, or heal. It launders. It launders reputations, it launders wealth, and it launders the sins of kleptocrats from Moscow to Baku. These professionals—lawyers, accountants, PR specialists, and citizenship brokers—are the unacknowledged foot soldiers of a global system of corruption. And in Indulging Kleptocracy: British Service Providers, Postcommunist Elites, and the Enabling of Corruption, authors John Heathershaw, Tena Prelec, and Tom Mayne finally shine a harsh spotlight on them.

If you’ve followed the breadcrumb trail of investigative journalism over the past two decades, you’ll have seen this story unfold in parts. From Londongrad in 2009 to Kleptopia and Butler to the World, the narrative has been clear: London is not just a passive recipient of dirty money—it’s an enthusiastic facilitator. What Indulging Kleptocracy does differently is focus not on the flashy oligarchs, but on the gray-suited enablers who make kleptocracy work in the West.

Let’s be honest. London didn’t become a haven for the world’s blood money by accident. This was a deliberate pivot. As the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s and post-communist elites scrambled to secure their wealth, the City of London—still licking its wounds from the decline of British manufacturing—stood ready. Deregulation of financial markets and a legal system rooted in property rights created the perfect environment for a new kind of client: the kleptocrat.

But where there is illicit wealth, there are also respectable professionals willing to serve it—quietly, efficiently, and without asking too many questions. The brilliance of Indulging Kleptocracy lies in its willingness to interrogate these professions: the ones who hold the door open while corruption strolls in.

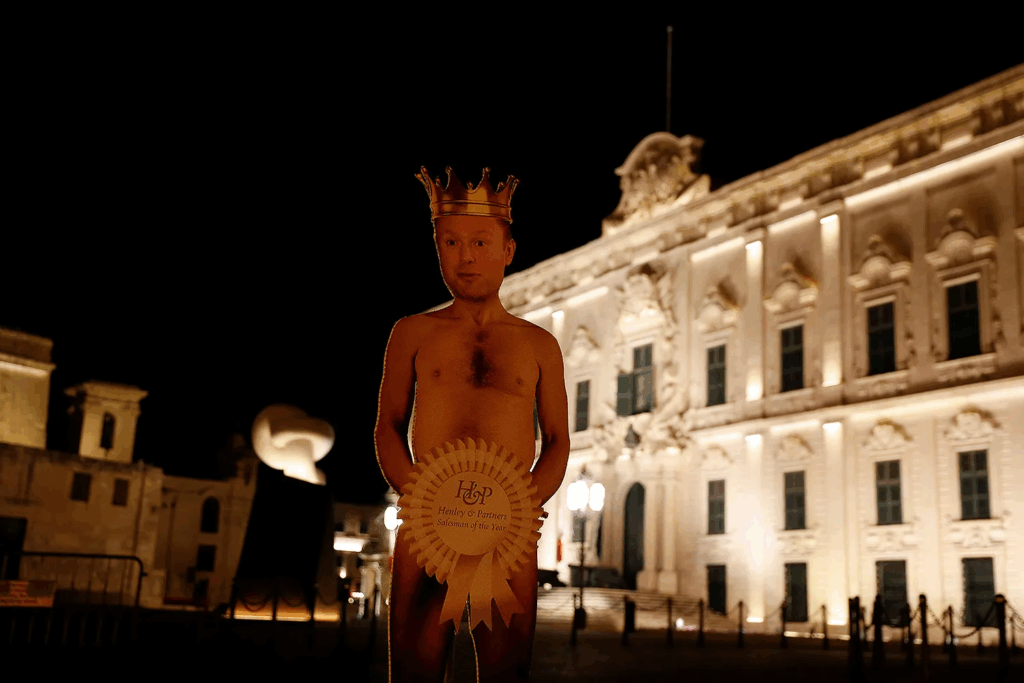

One standout example is Henley & Partners, a U.K.-based firm that sells citizenship like others sell luxury cars. Their business model is both simple and chilling: connect wealthy individuals—often from kleptocratic regimes—with passports from compliant states like St. Kitts and Nevis, Malta, or Cyprus. In one case, they helped process citizenship for Jho Low, the infamous Malaysian financier behind the 1MDB scandal. At one point, Low held a passport from St. Kitts and Nevis and was applying for one from Cyprus—with Henley’s help.

The firm insists there’s no “systemic problem,” claiming it merely facilitates legal government programs. But as the book astutely notes, such actors are not just passive players responding to demand—they are shaping the market, creating pipelines for illicit wealth to flow into the global system with a legitimacy veneer.

And these are just the citizenship brokers. The book meticulously catalogs nine ways enablers grease kleptocracy’s wheels: hiding money, setting up shell companies, laundering reputations, and silencing critics. The work is sometimes subtle, often legal, and nearly always shielded from public scrutiny.

A particularly damning anecdote comes from a Channel 4 undercover investigation, in which a London estate agent candidly told a client, “Don’t talk to me about how [the money] comes here.” It’s a level of willful ignorance that borders on complicity. And it’s not rare. In Britain, due diligence checks are often cursory. The professionals who facilitate these transactions are rarely held to account, even as they collect generous fees and commissions.

But this isn’t just a story about individual greed—it’s about systemic failure. The U.K.’s outdated libel laws, for example, make it perilously easy for oligarchs to sue journalists into silence. British courts don’t require a claimant to prove falsehood—only that a statement might damage their reputation. This has led to widespread self-censorship in media outlets, especially when reporting on the wealth and behavior of post-Soviet elites.

So why has so little been done to stem the tide?

Part of the answer lies in Britain’s own economic insecurity. Post-2008 austerity hollowed out public services, and Brexit compounded financial uncertainty. Against this backdrop, the influx of foreign capital—however shady—offered a tempting lifeline. Successive governments, regardless of party, have talked tough on corruption while quietly accommodating it. As Indulging Kleptocracy bluntly puts it, “The state is present at least by its absence.”

Even when action is taken, it’s reactive and piecemeal. The seizure of a Russian oligarch’s yacht in 2022, for example, made headlines. But for every high-profile sanction, there are dozens of lesser-known transactions that go unchecked. Meanwhile, the market continues to innovate faster than regulators can respond.

But the authors don’t stop at diagnosis—they offer a prescription. The key, they argue, is to treat kleptocracy as organized crime. Italy did it in the 1980s with the mafia, and Britain can do the same now. If someone is closely tied to a regime known for corruption, there should be a legal presumption that their assets are suspect. This would shift the burden of proof and make it harder for enablers to claim ignorance.

It’s a provocative suggestion, and one likely to meet resistance from powerful quarters. But it’s also necessary. Because if nothing changes, Britain risks becoming a parody of its own values—a country that lectures the world on democracy and transparency while selling its soul for Russian rubles and Azeri petrodollars.

That said, the book doesn’t strike a tone of revolutionary outrage. Its conclusions are, in a sense, depressingly realistic. The authors acknowledge that “to indulge no more may be too big an ask.” The best we might hope for, they say, is “to indulge a little less.”

It’s a low bar. But in a country where oligarch money buys townhouses, influence, and silence, even that would be a step forward.

If there is a silver lining, it’s that the public mood is shifting. The war in Ukraine has made Western societies far less tolerant of dubious Russian wealth. There’s growing recognition that the same systems that enable kleptocrats to hide their loot also weaken democracy and hollow out public institutions.

But awareness isn’t enough. Laws must change. Transparency must become more than a buzzword. And most importantly, we must stop pretending that corruption is something that happens over there. It’s here. It’s on our high streets, in our banks, behind the plate glass of luxury real estate firms. And it won’t go away until we start holding the enablers accountable.

Because kleptocrats may be the face of corruption—but they’re not the whole body. For that, we need to look a little closer to home.

References and Further Reading

- Oxford University Press – Book Listing

Official publication details and synopsis of Indulging Kleptocracy.

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/indulging-kleptocracy-9780197688229 - Foreign Policy: “The Kleptocrat’s Sidekick”

An investigative piece on Henley & Partners and their role in facilitating citizenship for kleptocrats.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/04/18/kleptocracy-london-dirty-money-uk-enablers-corruption - The Guardian: “London estate agents caught on camera dealing with ‘corrupt’ buyers”

A Channel 4 investigation revealing estate agents’ complicity in money laundering.

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jul/07/london-estate-agents-caught-on-camera-russian-buyer - OpenDemocracy: “SLAPP: How UK libel law helps oligarchs silence journalists”

An analysis of how British defamation laws are exploited to suppress investigative journalism.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oliver-bullough-oligarchs-libel-journalism-slapp - Transparency International UK – What We Do

An overview of efforts to combat corruption and promote transparency in the UK.

https://www.transparency.org.uk/what-we-do - Journal of Democracy: “The Rise of Kleptocracy: Laundering Cash, Whitewashing Reputations”

An academic exploration of how kleptocrats use global systems to legitimize illicit wealth.

https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-rise-of-kleptocracy-laundering-cash-whitewashing-reputations - The Guardian: “Senior media figures call for law to stop oligarchs silencing UK journalists”

A report on calls to reform UK libel laws to protect journalistic freedom.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2022/nov/29/slapps-senior-media-figures-call-for-law-stop-oligarchs-silencing-uk-journalists - Morgan Lewis: “UK and European Taskforce Emerges to Expand Anti-Corruption”

Details on the formation of a new taskforce aimed at combating corruption in the UK and Europe.

https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2025/04/uk-and-european-taskforce-emerges-to-expand-anti-corruption-as-us-looks-to-scale-back - Phys.org: “Powerful legal and financial services enable kleptocracy”

Research highlighting the role of British service providers in facilitating kleptocratic practices.

https://phys.org/news/2025-02-powerful-legal-financial-enable-kleptocracy.html - The Guardian: “Malta still selling golden passports to rich stay-away ‘residents'”

An investigation into Malta’s citizenship-by-investment program and its exploitation.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/23/malta-still-selling-golden-passports-to-rich-stay-away-residents - Transparency International UK: “UK Government announces ‘clamp down on corruption and illicit finance'”

Announcement of UK government initiatives to tackle corruption and illicit financial flows.

https://www.transparency.org.uk/news/uk-government-announces-clamp-down-corruption-and-illicit-finance - The Bureau of Investigative Journalism: “Silencers of the truth: what are SLAPPS?”

An explainer on Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation and their impact on free speech.

https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/explainers/silencers-of-the-truth-what-are-slapps - The Guardian: “Ukraine war ‘opening eyes’ to need to reform England’s libel laws”

Discussion on how geopolitical events are influencing calls for libel law reforms in England.

[https://www.theguardian.com/law/2023/jan/31/russia-ukraine-war-reveals-englands-draconian-libel-laws-says-lawyer](https://www.theguardian.com/law/2023