As the European Union prepares to finalize its latest round of sanctions against Russia, aimed at weakening the Kremlin’s war machine, Slovakia finds itself in an unenviable position — standing at the crossroads of European unity and economic survival.

Prime Minister Robert Fico’s cautious approach to the EU’s proposed sanctions package, particularly the plan to end Russian gas imports by 2028, has sparked frustration in some European capitals. But beneath the headlines lies a fundamental truth: no sanctions regime can succeed if it crushes the very member states tasked with upholding it.

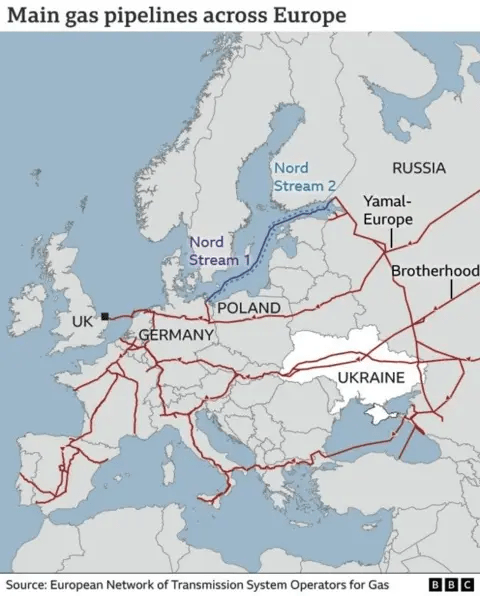

Slovakia relies heavily on Russian gas — a legacy of geography, infrastructure, and decades of dependency shaped during the Soviet era. A sudden shift away from that supply chain, without adequate support or alternatives, risks plunging the Slovak economy into an energy crisis. It is not only reasonable but responsible for Fico to demand guarantees from the European Commission and Slovakia’s partners before endorsing the package.

“We need to win something in this fight,” Fico remarked, cutting to the heart of the matter. This isn’t about defiance or sympathy for Moscow; it’s about ensuring that Slovakia does not become collateral damage in Europe’s geopolitical reckoning. His call for a cap on fees for alternate supply routes, and for broader political commitments, reflects a pragmatic desire to share the burdens of transition, not to avoid them.

This stance should not be mistaken for obstructionism. In fact, Fico has made clear that Slovakia is not ruling out support for the sanctions — only that such support must come with mechanisms to mitigate disproportionate impacts. That is not sabotage; it is statesmanship.

The EU, in its quest for moral clarity and strategic coherence, must not lose sight of the economic disparities among its members. Sanctions, while powerful tools of pressure, are blunt instruments if not paired with solidarity. If smaller, more vulnerable economies are expected to bear the same burdens as larger, more diversified ones, cracks in the European project will only deepen.

Germany and Poland — two countries with significant political and economic weight — have reportedly been in talks with Fico. This is encouraging. It shows that even in moments of tension, diplomacy can prevail. The EU must now follow through and show that unity is not about uniformity, but about mutual support.

Slovakia’s dilemma is Europe’s dilemma writ small. The path away from Russian energy dependence will be long and uneven, but it must be walked together. If that means tailoring support packages, capping fees, or creating flexible timelines for the most exposed economies, so be it.

Sanctions are not only a tool to punish — they are a test of resilience, coherence, and empathy. If Europe fails to support Slovakia now, it sends a dangerous message: that unity stops at the border of economic pain.

That is a risk the EU cannot afford.