A political standoff on Capitol Hill now threatens one of the nation’s most reliable sources of early-stage innovation funding. As Congress debates the future of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, proposals intended to “fix” it may instead strip away what has made America’s seed fund so uniquely effective for more than four decades.

At the center of the fight is a philosophical divide. Senate Republicans, led by Sen. Joni Ernst (R-IA), want to install new guardrails, arguing the program has been exploited by firms that rely on SBIR awards as a business model rather than a springboard. Senate Democrats, led by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA), insist that the program’s current structure works. The House, for its part, is pushing simply to keep the program alive with a one-year extension.

Meanwhile, some well-meaning intermediaries are searching for a compromise. Their idea: judge the success of SBIR projects by a single criterion—whether the resulting technology becomes a formal Program of Record inside a federal agency. In other words, tie SBIR funding to government adoption alone.

It’s a simple proposal. It is also a dangerous one.

A Narrow Metric for a Wide Mission

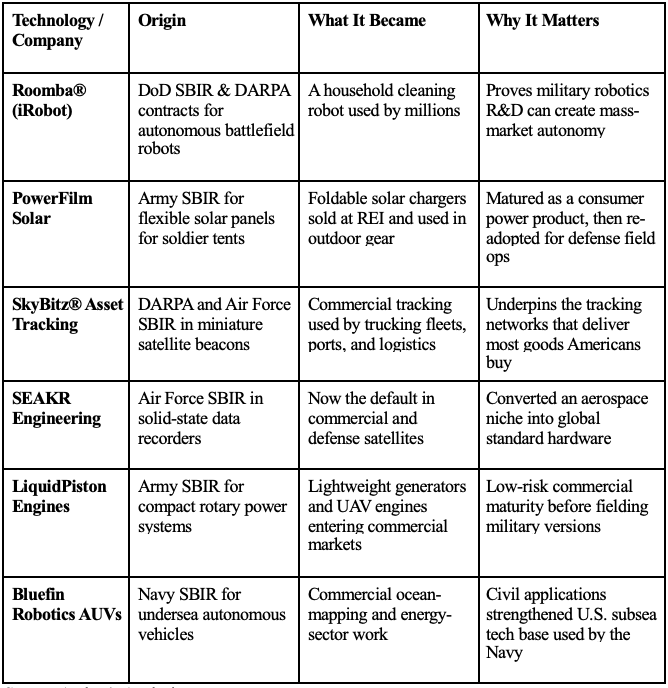

The SBIR program exists to help small companies turn research concepts into working, testable products. For decades, that model has produced breakthroughs that often begin in federal labs but flourish in commercial markets—only to return later as mature technologies the government can adopt at lower cost and lower risk.

There are two fundamentally different pathways for an SBIR project to succeed:

- Government pull, in which an agency becomes the first buyer.

- Commercial pull, in which private markets validate and scale the technology before the government ever signs a contract.

Both matter. But the second pathway—commercial success—is where the American innovation economy gains the greatest multiplier effect. According to the National Academy of Sciences, about one-third of SBIR-funded companies ultimately sell products either commercially or to the government, and each federal dollar invested generates as much as $7–$9 in follow-on revenue or private capital.

That isn’t waste. It is precisely the leverage SBIR was designed to achieve.

Reducing the program to a single government-transition metric risks turning what is meant to be a diverse portfolio of bets into a narrow contracting pipeline. It would push companies toward safe, incremental proposals designed to satisfy acquisition offices rather than push technological boundaries. And it would send a clear message to private investors: this is no longer a market signal worth watching.

The Cost of Distorting an Innovation Pipeline

If Congress enshrined government adoption as the only hallmark of success, the ripple effects would be immediate:

- Startups would prioritize low-risk projects that agencies already expect to buy.

- Federal offices would over-engineer transition plans, creating yet another bureaucratic hoop.

- Private capital would retreat, eliminating the external validation that de-risks public investment.

The irony is that SBIR was originally created to prevent exactly this kind of insularity. Many of the technologies Americans use every day—tools that once seemed speculative—emerged from SBIR projects that first found traction far outside the Pentagon.

The lesson is clear: the program’s power lies in cultivating options, not narrowing them.

Reform Without Ruin

None of this means the program should remain untouched. Concerns about so-called “SBIR Mills”—firms that string together award after award without meaningful progress—are real. Sen. Ernst’s proposal to cap the lifetime number of awards a company can receive would curb this behavior without choking off innovation.

Congress could also strengthen portfolio-level oversight. High-performing SBIR offices, such as the Navy’s, already track outcomes like user engagement, follow-on investment, prototype performance, and early adoption milestones. But managing innovation well requires resources, and many SBIR offices lack the staffing and flexibility to do it. A modest legislative adjustment to the program’s spending cap could empower agencies to measure impact instead of merely processing applications.

Keep America’s Seed Fund Rooted in Experimentation

SBIR was never meant to be a procurement tool. It was built to fund thousands of experiments, accepting that many would fail while a few would become transformative. That diversity—of ideas, of technical approaches, of market paths—is what has kept America ahead.

To reduce SBIR to a one-track race would be to prune a tree not by shaping its branches, but by cutting its roots.

If Congress wants reform, it should follow a balanced path: adopt accountability measures that discourage rent-seeking, while preserving commercialization as an equal—often superior—marker of success. When a small company wins in the commercial marketplace, the country wins twice: innovation accelerates, and the government gains access to mature technology without footing the full development bill.

America’s seed fund doesn’t need to be reinvented. It needs to be allowed to grow.