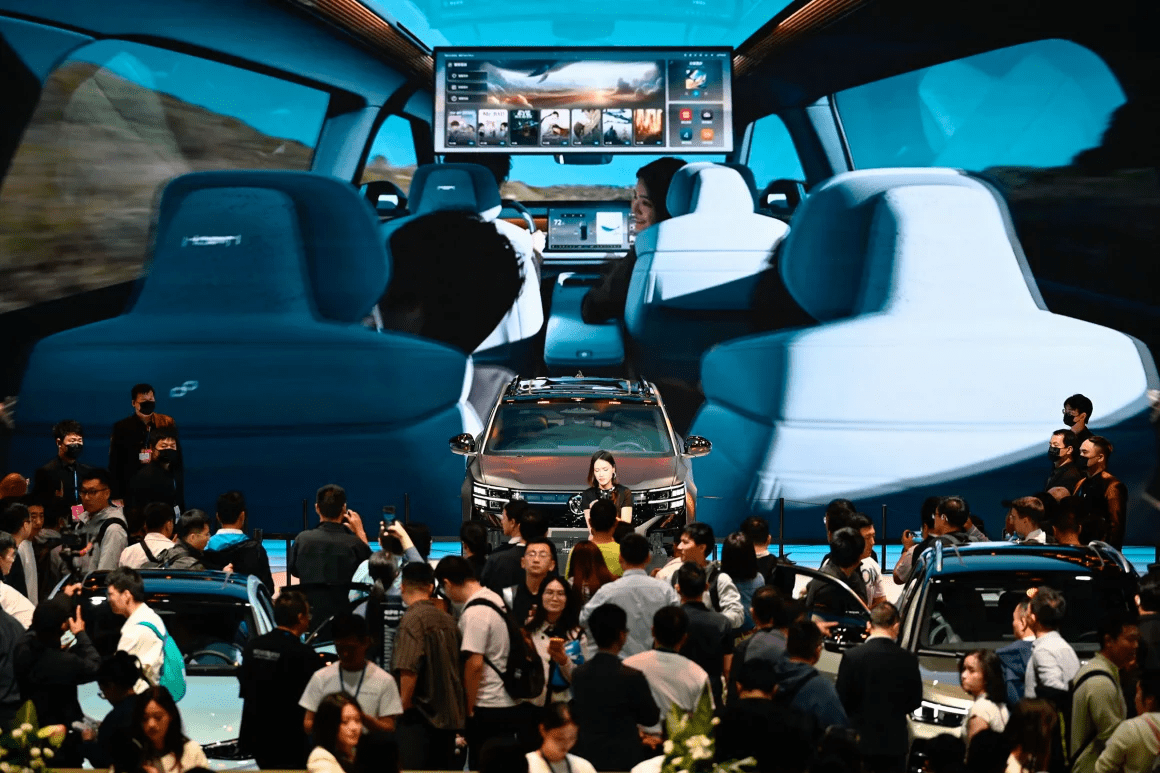

At the Shanghai auto show this spring, the message from China’s carmakers couldn’t have been clearer: the age of China as a mere manufacturing hub is over. It is now an innovator—arguably the innovator—of the global automotive future.

Inside the sprawling exhibition, where bass-heavy soundtracks accompanied flying cars and 5-minute EV charging demos, it wasn’t Volkswagen or Ford drawing the crowds. It was BYD, Xiaomi, Nio, and dozens of other Chinese electric vehicle (EV) makers unveiling models that look and feel as futuristic as they are affordable. Meanwhile, outside the glitz and neon, China quietly exported nearly half a million EVs in just the first three months of the year.

This is more than a spectacle of engineering—it’s a demonstration of economic reordering. For years, China was cast as the imitator, a land of cheap labor and clunky knock-offs. Now, it’s building vehicles that outperform, outprice, and outmaneuver legacy brands in markets from Southeast Asia to South America. And it’s doing it with breakneck speed.

As Washington ramps up tariffs on Chinese-made vehicles and auto parts—most recently under Donald Trump’s revived trade offensive—it risks not just a trade war, but a technological Cold War that could isolate the U.S. from the fastest-growing EV innovation on Earth. While American policymakers tighten the screws, Chinese firms are innovating, iterating, and expanding.

Yes, Beijing’s industrial policy deserves scrutiny. Generous subsidies, raw material monopolies, and export-oriented production targets have fueled China’s EV rise. But dismissing this transformation as a product of state support alone is a dangerous oversimplification. It also ignores something more potent: competition.

Inside China’s borders, a cutthroat price war among dozens of EV firms has driven relentless innovation. Companies like CATL and BYD are trading punches with breakthroughs like 5-minute charging batteries that offer over 300 miles of range. Firms are racing to integrate autonomous driving tech, luxury-grade interiors, and next-gen infotainment into cars that sell for under $30,000. It’s the kind of market pressure that breeds not just affordability, but excellence.

Compare that to the U.S., where political backlash against EVs is growing, federal support is inconsistent, and the leading domestic player—Tesla—has been losing ground to Chinese rivals in both innovation and sales. Even Tesla, which once defined the EV category, skipped the Shanghai show, ceding the global spotlight to China’s new champions.

In fact, BYD—the company Warren Buffett bet on in 2008—just outsold Tesla last year. Its CEO Wang Chuanfu, who started as a battery engineer, cried on stage while declaring the era of Chinese cars had arrived. His emotion wasn’t performative. It was prophetic.

Now, China controls over 60% of the global EV market. In Thailand, customers are ditching Toyotas for BYDs. In Europe, Chinese cars are increasingly present on city streets. Even legacy Western automakers are forming joint ventures with Chinese firms—Volkswagen with XPeng, GM with Momenta—to tap into the country’s technological edge.

But here’s the rub: while Chinese firms move outward, the U.S. is turning inward. Trade walls, export controls, and political posturing may win points at rallies, but they won’t stop progress. At best, they delay the inevitable; at worst, they cede global leadership to others.

If the U.S. doesn’t recalibrate, it risks becoming, in the words of one U.S. expert, “an island of tailpipes in a world of batteries.” That’s not just a climate setback—it’s an economic and technological one.

America once led the world in auto innovation. The question now is whether it wants to lead again—or get left behind as the road to the future detours through Shanghai.